Page originally created in July 2011 and last updated: 9th February 2025

Inner-city Serpent - 3.5ft adult female Aesculapian Snake at Regent's Canal, London, 2016

Aesculapian Snake (Zamenis longissimus, previously Elaphe longissima & Coluber longissimus)

Here in the UK we have three native snake species and one, or possibly two, introduced species of snake that have established breeding colonies at specific sites. The five snake species found are:

Native: Adder / Northern Viper (Vipera berus), Barred Grass Snake (Natrix helvetica), Smooth Snake (Coronella austriaca)

Introduced: Aesculapian Snake (Zamenis longissimus), Eastern Romanian Grass Snake (Possibly Natrix natrix persa)

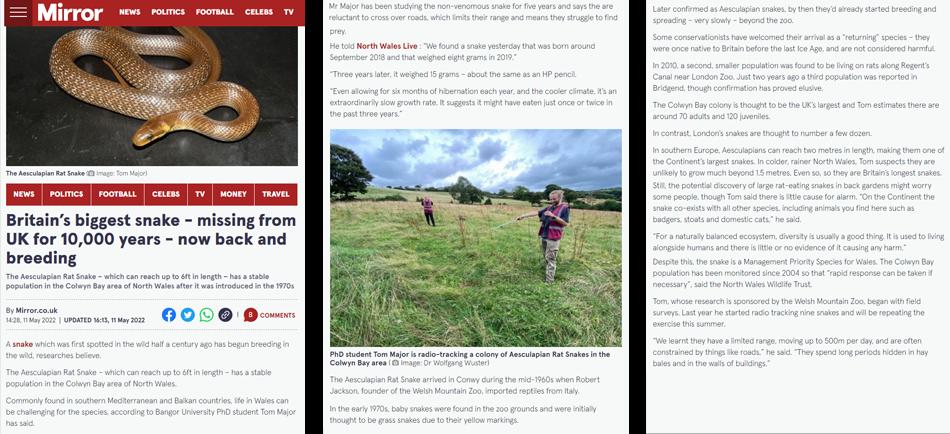

The fourth snake is the introduced Aesculapian Rat Snake. Aesculapian Snakes are originally from mainland Europe, but small colonies are currently established in two specific parts of the UK. Aesculapian Snakes haven't been resident in the UK for at least 20,000 years, and probably more than 120,000 years, and they are now considered by Natural England to be non-native to the UK. However, there are two well established breeding colonies of Aesculapian Snakes here in Great Britain that have been in existence now for over 35 years. The oldest introduced colony of Aesculapian Snakes in the UK, is in Colwyn Bay, North Wales. The second colony is in Camden, Central London, in England. Outside of the UK the nearest populations of wild and native Aesculapian Snakes are found in northern France.

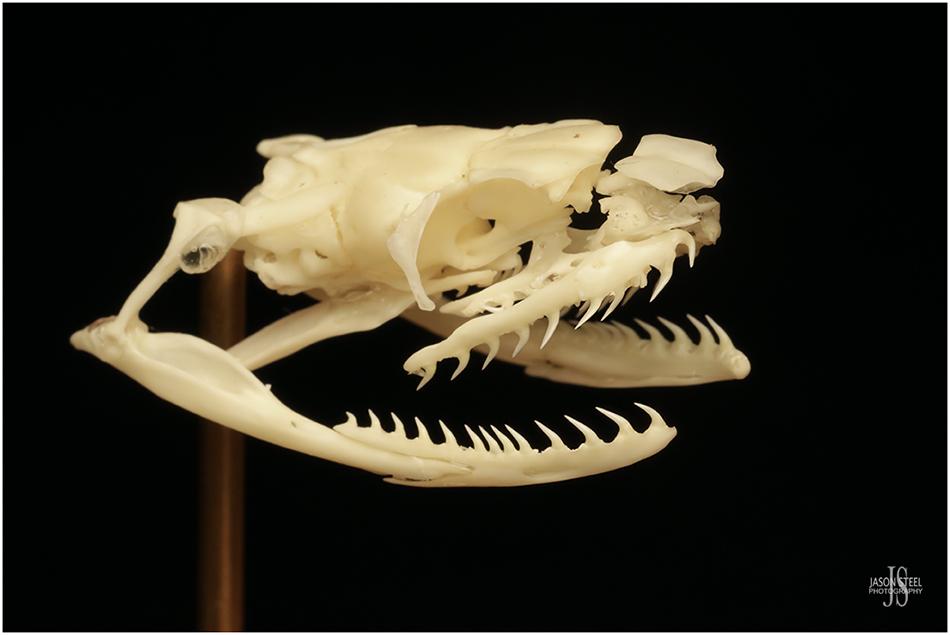

These long slender Rat Snakes, of the Colubridae family, are Old World Snakes and are one of Europe's longest snakes. They regularly grow to a length of 140-160cm. In warmer parts of Europe they can reach up to 180cm and have even reached 225cm on one occasion. This easily makes them the longest snake found in the UK, and one of the longest in Europe. The maximum weight for males is usually around 890 grams and 550 grams for females. These snakes are usually found across southern, central and eastern Europe and prefer the same method of incubating their eggs as our native Grass Snakes, using warm damp moist areas of rotting vegetation, such as hay piles and compost heaps, to provide the necessary heat. Aesculapian Snakes are the only semi-arboreal snake in Europe. Not only are they are excellent climbers but are equally at home high up in trees and bushes as they are on the ground. They can on occasion be found basking on the canopies of trees and tall bushes, or on roof-tops of buildings in their native range. In Europe they are regularly encountered on the edges of Beech and Oak forests at lower altitudes, as well as open grass fields and meadows surrounded by bushes, and dry stone walls. They can also be found in shrubs that border lakes and river banks.

Male Aesculapian Snake at Regents Canal, London. 2020

So where did they come from and how did the two separate populations of Aesculapian Snakes end up here in the UK?

1) Colwyn Bay population of Aesculapian Snakes in North Wales.

In 2006 the Welsh colony of Aesculapian Snakes was estimated at around 85 adult and 365 juvenile specimens, and originally came about during the early 1960's after a gravid female snake, affectionately referred to as "Old Essie" by the 2003 assistant curator Peter Dickinson, escaped from the Welsh Mountain Zoo at Colwyn Bay and laid her eggs within the grounds of the zoo. The offspring then successfully bred and the population has thrived ever since in and around the zoo grounds. The first feral snake born within the grounds of the Welsh Mountain Zoo was found crossing a pathway within the grounds of the zoo in 1963, and was quickly identified as an Aesculapian Snake. It is quite possible that this colony derived from more than just one escaped specimen though. According to the NNSS website the first official record of these snakes living wild in Colwyn Bay was in 1970. They were first reported by the press during the early '70's. Software analysis has however suggested that several individual specimens probably comprised the founder stock rather than just one specimen according to the 2009 book "The Naturalised Animals Of Britain & Ireland" by Christopher Lever. Since its introduction this colony has not spread far from the zoo in its 60 years of existence, confirming that this species probably has a low dispersal ability, and is reliant on woodland connectivity to travel. It is also very likely that due to the abundance of rodent prey surrounding the Colwyn Bay Zoo that these snakes are reluctant to leave this food-rich location. The main egg laying site for this snake population had long been suspected to be the manure dump at the Zoo. Ongoing studies revealed in 2021 that these snakes are using both the zoo's manure dump and offsite compost heaps as egg-laying sites.

The Welsh Mountain Zoo at Colwyn Bay was founded in 1963 by Robert Jackson. Robert Jackson was an importer and dealer of reptiles, amphibians, mammals and birds. One of the many species he sold in the 1950's & 60's was the Aesculapian Snake. See link here

The Colwyn Bay colony of Aesculapian Snakes is now the most northerly colony of this species currently found in existence anywhere in the world. Historically though the Aesculapian Snake's range once extended as far north as NW Denmark, which is even further north than Edinburgh would be in the UK.

2) London colony of Aesculapian Snakes.

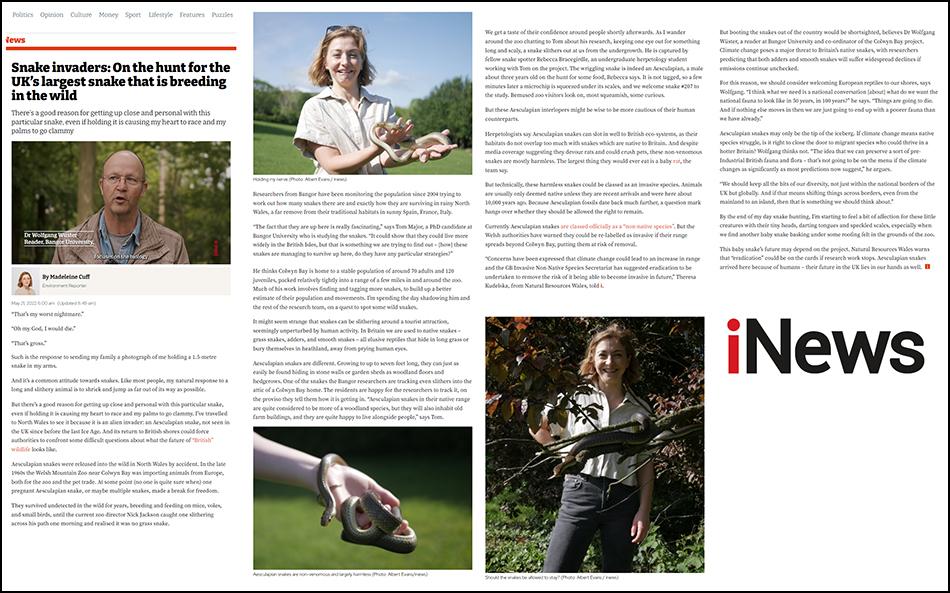

I have personally been studying and photographing the Aesculapian Snakes in London for thirteen years now, since 2011. My sightings and observations have continually been added to the database held by Will Atkins, as have records that I have forwarded to Will from other sightings by members of the public. By 2018 the London population of Aesculapian Snakes had seen 50 different adult specimens recorded and photographed, and in 2013 this population was then estimated at around 40 specimens. However the number of these urbanised snakes seems to have fallen significantly in London over recent years. Between 2016 -2021 the number of sightings has seen a definite decline and there are serious concerns as to how many of this once thriving population of feral snakes may still exist in 2023. This population is confined to a small area of around two hectares in Central London, surrounded by busy roads, and could only spread beyond this range by travelling great distances along Regents Canal itself, or by crossing these busy roads. During 2022 and 2023 the number of sightings did seem to be increasing, but this may just be because theses snakes are becoming less fearful of humans due to constant exposure to high levels of human traffic along the canal tow-path at Regents Canal. Public awareness of the species has increased significantly in recent years, due to coverage from the British media, and from sightings being shared on social media platforms such as Facebook and TikTok. This has led to a huge increase in the number of people actively looking for these snakes to photograph for themselves.

With the feral population of London Aesculapian Snakes being found in, and very close to, the grounds of London Zoo it would be easy for one to jump to conclusions. But despite the obvious theory that the London population of Aesculapian Snakes must have derived from one or more escapees from London Zoo, this surprisingly isn't the case.

So if these snakes didn't originate as escapees from London Zoo then how did they get there? It is widely accepted that this population came about after about eight individual specimens of Aesculapian Snake were deliberately released along the banks of Regent's Canal in the mid 1980's from the "Centre For Life Studies", a building located at Zoological Gardens, Regents Park, NW1, adjacent to London Zoo, and rented by ILEA (Inner London Education Authority facility for scientific experiments). Within the circles of respected herpetologists, some still claim to know exactly which former ILEA staff member was responsible for releasing these snakes onto the banks of Regent's Canal. However some former ILEA employees insisted that these snakes escaped and were not deliberately released.

After repeated sightings of an unknown snake species along the banks of Regents Canal during the 1990s theses snakes were finally identified from photographs, and in 1998 reported to TESL by Ester Wenman, who was at that time the head keeper of reptiles at London Zoo. This growing population of Aesculapians in London became common knowledge amongst many herpetologists in April 2007, via a popular online British herpetology forum, Reptiles & Amphibians UK, and many herpetologists travelled to London to find and photograph these snakes for themselves.

In an interview with the Camden Review in 2010 David Bird, a former zoo curator, also told the reporter that the Aesculapian Snakes either escaped from or were deliberately released from the ILEA building: Camden Review article

Christopher Lever discussed the London Aesculapians in his 2009 book "The Naturalised Animals Of Britain & Ireland" by Christopher Lever", and Will Atkins & Tom Langton then went into more detail about the origins of the London Aesculapian Snakes in 2011 when they wrote a detailed account in The London Naturalist No.90, 2011 on pages 93-95, giving this summary:

"A second feral population has been extant since the mid 1980s along a canal embankment habitat in Camden, north London. This was first reported to TESL in 1998 by Ester Wenman, then head keeper of reptiles at London Zoo. Aesculapian snakes had apparently colonised the area during an experiment reported by the British Herpetological Society Legal Officer, Peter Curry, who was working there and keeping this species at the Inner London Education Authority Centre for Life Studies at the time that it was closed down around 1986. One account was that eight snakes had been released ‘on the quiet’ around the time of closure to try to form a population, several of which were recaptured, but some remained at large. Those caught initially were being euthanized but the view was then taken to leave the others ‘to take their chances’ where they were. Ten years later, in an aviary close to the embankment, fragments of juvenile Aesculapian snakes were found in a laughing thrush Garrulax sp. aviary, suggesting that the snakes had bred." The article also states, “Several newly born snakes were found in the basement of a building around 30 metres from the embankment in 2010, and breeding in that year was also shown in 2011 with a young 2010 cohort snake being located. To this date this is the only example of a non-native snake species breeding successfully and forming populations in the wild in London and the UK as a whole.”

A ZSL reptile keeper, who was working at London Zoo at the time when these snakes were released, claims these snakes were actually "deliberately released quite a while before the ILEA building was shut down". He claimed that during the 1990's the Aesculapian Snakes that were found by ZSL staff on the south bank of the canal would be captured and re-released back on the north bank of the canal, where the ILEA building was. One herpetologist ,that claims to have been close friends with the ILEA staff member who released the snakes at Regents Canal, has gone into more detail about the origins of the London Aesculapian Snakes. In 2022 he has publicly stated: "The person responsible for their release was a personal friend of mine for many years. The original specimens were collected from the wild in Italy (when it was still legal to do this). We do not know precisely how many snakes were released but with a little more research, we should be able to trace the locality they were originally collected from."

Natural England were slow to accept the existence of the London Aesculapian Snake colony. In their 22nd May 2009 report "Horizon scanning for new invasive non-native animal species in England", they discussed the Welsh colony of Aesculapian Snakes and went on to comment on the London colony saying " There are also anecdotal reports of individuals of this species in central London".

The London Naturalist No.99, 2020, page 96 & 97

In November 2020 the 99th edition of The London Naturalist published a lengthy update on the London Aesculapian Snake colony, by Will Atkins, The article was compiled using data based on Will's own sightings of the Aesculapian Snakes at London, as well as records that were submitted by myself and others. Will was the first to study these snakes and his knowledge during the earlier years of the London Aesculapian Snakes is second to none. His well written and in-depth article mentioned many points that I have also written about on this website. Will's views and opinions often echoed that of my own when discussing the conservation status and fears for the future of these snakes in the UK.

Are there any other colonies of Aesculapian Snake anywhere else in the UK?

The simple answer to this question is no, there currently aren't.

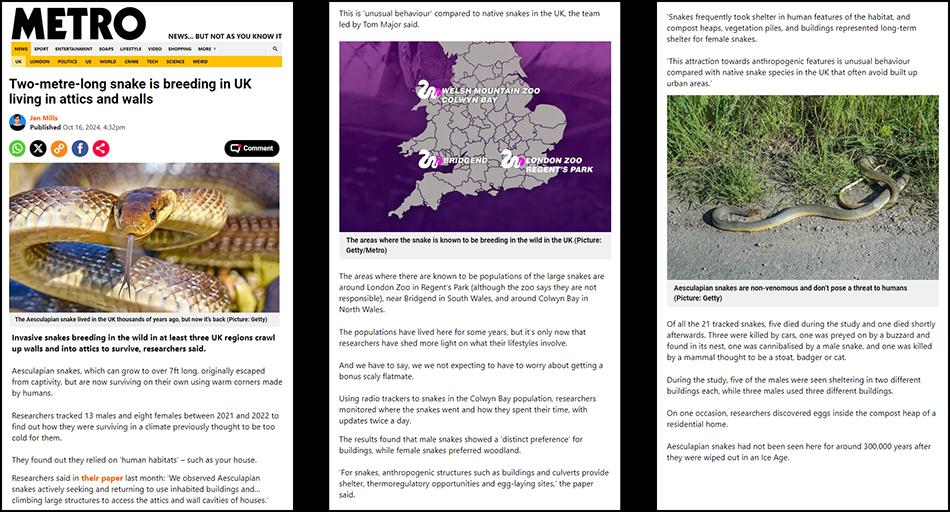

What about the reported Aesculapian Snake colony at Bridgend, in South Wales?

On July 1st 2020 it was announced by Steven Allain, and Dave Clemens, that the British Herpetological Society had published their paper in issue 152, Summer 2020, of the Herpetological Bulletin. This paper announced a possible third population of Aesculapian Snakes living wild and breeding here in the UK. - LINK

There was already the oldest UK Aesculapian Snake colony in North Wales but in 2020 there was great excitement around this potential new colony at Bridgend, South Wales. The two reported Welsh colonies of Aesculapian Snake were nearly 200 miles apart. This is almost the same distance as the London Aesculapian Snake colony is from the Bridgend colony.

The first report of an Aesculapian Snake to be found in Bridgend came from a member of the public after an adult snake was reported as found in a residential garden on the 19th September 2016, although this wasn't made public knowledge until nearly four years later. Further investigation found that these Aesculapian Snakes were also reportedly present at nearby allotments. When questioned at the time local residents claimed that these snakes had been known to have been around in their area for around 15 - 20 years. With a railway line nearby this feral population of Aesculapian Snakes differed from the other two populations found in the UK because it had the potential to disperse and spread considerably further from where it was reported to have been recorded.

There were many questions such as how many Aesculapian Snakes there were in Bridgend, or how far they may have spread. It was also unknown how these snakes came to be in the area. The paper by S.Allain & D.Clemens mentioned the possibility that the founding snake / snakes could be escaped pets or a deliberate release. Surveys and studies were carried out by ARC-Trust in an attempt to answer these questions. However, since being reported in 2020 there were no new sightings of any Aesculapian Snakes in the area, despite extensive surveys being performed for them during 2021. The lack of sightings was possibly attributed to the CV19 lockdowns of 2020 and 2021, and it was hoped that as time went on more sightings would be recorded. In 2023 it was finally revealed that the entire story had been a hoax. The initial record was submitted by a member of the public who had photographed an Aesculapian Snake whilst on holiday in Europe, and then falsely claimed that the snake had been seen in south Wales. All other claimed sightings, that came from local allotment keepers and gardeners, were a case of mistaken identity, confusing native Grass Snakes in the area, for introduced Aesculapian Snakes.

Other sightings in the UK

On Sunday 13th June 2021 a post was added to Facebook by Jack Dabney clearing showing a photo of a wild Aesculapian Snake, seen climbing a wall in Ilfracombe, north Devon, on a sunny day that saw a temperature of 22 degrees. Jack claimed the snake was about 5ft in length. Other people were quick to reply to the post claiming also to have also seen similar snakes in the area. Whether these other claimed sightings were also of Aesculapian Snakes or of other native snake species is currently unknown. In 2021 it was unknown whether the definite sighting in Ilfracombe was an isolated specimen or whether there may have been a fourth colony of these beautiful snakes waiting to be discovered in the UK. The former Ilfracombe Zoo existed in that area until 1973, so if more specimens were to be found in Ilfracombe then the question could be asked whether the zoo may have once accidentally been responsible for origins of a possible Aesculapian Snake colony in the area? However, since that one original sighting in 2021 there have been no further reported sightings in the area.

This finding was shared to the UKARGS Facebook group by Ryan Holder, a local to the Devon area. LIINK. Alexandros Theodorou replied to the Facebook post that "There was also a record of an Aesculapian Snake near Weymouth while I was doing my Masters on them in 2016". Anthony Plettenberg also reinforced this comment by saying "On the other side of the peninsula, there was an adult found in 2016 in Weymouth. Similar situation - photographed, ID'd online, and probably still there". The 2016 Weymouth sighting was actually a juvenile specimen found early one morning by a member of the public in a carpark in Charlestown, Weymouth. However, with a local pet store & reptile specialist just a couple of hundred metres away from where this Aesculapian Snake was found it does make one question whether the snake may have escaped from there?

Jason Steel photographing an adult female Aesculapian Snake along Regents Canal in London, UK in 2016. Photo taken by Australian photographer Diane Paine.

Are Aesculapian Snakes an invasive species, and are they a threat to our native wildlife?

The simple answer to this question is no, not at all. For a species to be classed as invasive it firstly needs to be spreading, which neither of the UK colonies really are. Secondly, it needs to be having a detrimental effect on our native species, which these snakes are not.

Following ongoing studies of these Aesculapian Snake populations in the UK by herpetologists including Wolfgang Wüster and Tom Major in Bangor, Wales, & Will Atkins and myself in London, it is clear that the existence of these snakes has had very little if any negative impact on our native wildlife. This is largely because in the UK they feed almost entirely on common rodents, which are found in abundance around both zoos. Whilst Zamenis longissimus are considered to be generalist predators their primary prey in London is the Brown Rat, Rattus norvegicus. The Brown Rat is a non-native species in the UK that was accidentally introduced to the British Isles around 1720, as a stowaway aboard sailing ships. LINK

In 2016 one adult Aesculapian Snake specimen that was handled by a fellow amateur herpetologist, and friend of mine, quickly regurgitated six newly born rat pups. At this size the rat pups are far too young to leave their nest so this supports the knowledge that the Aesculapian Snakes are actively hunting rodents in their own burrows and hideaways. In 2021 another adult female Aesculapian Snake specimen, that was handled, regurgitated two young Brown Rats of 55mm & 60mm in body-length. Analysis of Aesculapian Snake droppings has also found traces of mouse hair. (The London Naturalist No.90, 2011, page 95). In 2021 studies of the Welsh colony of Aesculapian Snakes, by Tom Major & Bangor University, have revealed that these snakes have on occasion fed on ground nesting birds at that site too. Hatchling snakes there have fed on very young rodent pups. LINK It's been reported in Croatia, where these snakes are native, that adult Aesculapian Snakes can feed as often as every three days in the warmer months. LINK In their native range Aesculapian Snakes have also been known on occasion to feed on the eggs of ground nesting birds too. However, no such ground-nesting avian species exist in the vicinity of the London Aesculapian Snakes.

These snakes also seem dependent on woodland habitat connectivity in order to spread. In 60+ years since their arrival in the UK neither of these two populations of Aesculapian Snakes have been able to spread further than the sites where they are established. In London there simply aren't the necessary dispersal corridors available for the Aesculapian Snakes to disperse any further than they already have along the banks of the canal. And the population's distribution and reproduction is severely limited by the scarcity of suitable egg-laying sites.

It is largely down to the cooling climate over the past 5000 years that has seen a decrease in the distribution and numbers of Aesculapian Snakes across their native range in Continental Europe. With the undeniable current climate change, that is already here and taking place across the world, temperatures in recent years are now once again on the increase. It is likely that the natural range of the Aesculapian Snakes found in Europe will change in the future. As temperatures continue to rise it is likely that many reptile species in Continental Europe, including the Aesculapian Snakes, will attempt to move further north and once again inhabit areas where they were previously found, if they are not prevented from doing so by busy roads that divide the land and isolate reptile populations in so many places. In Austria, where the Aesculapian Snake is considered both native and endangered, the Aesculapian Snake has already been recorded since 2014 as expanding its range both further north and higher in altitude. Where previously it was only found up to 1000m above sea-level it has now increased its range to 1200m above sea level. The same behaviour is also being seen with Adders in Austria too. See link here.

With Aesculapian Snakes already present in the NW of France it is only the English Channel that prevents any possibility of theses snakes from returning to British soil of their own accord in future years. It is known from fossil records that Aesculapian Snakes have previously lived alongside our British native species in the past and given the opportunity could do so once again, probably without issue if they could reach our southern shores. Aesculapian Snakes are found across much of Europe living side-by-side with many of the same species of wildlife that we have in the UK without any issues so it is still very unlikely that Aesculapian Snakes could ever become a threat to other native species.

Adult female Aesculapian Snake at Regents Canal, London. 2016

Are these snakes dangerous to humans?

No, not at all. The Aesculapian Snake is non-venomous and not an aggressive species. It also lacks the size or strength to inflict any harm to either humans or pet cats & dogs. Unless you're a rodent, a small bird or a young lizard, then you're quite safe from these snakes, despite what the press would have you believe.

Very occasionally Aesculapian Snakes have been known to put on a fake threat display by rapidly shaking their tail and beating it against the ground to imitate a Rattlesnake. This is not something that I have ever witnessed myself but this behaviour was filmed by Priroda Sjevera in Montenegro, in July 2024. - LINK

Adult female Aesculapian Snake by Regent's Canal, London. 2016

Adult female Aesculapian Snake, Regent's Canal, London, 2016

It is believed that Aesculapian Snake specimens found in London tend to be slightly larger than those in Colwyn Bay and this could be one possible effect of in-breeding by the Welsh snakes, if there is truth in the rumour that the Welsh population of Aesculapian Snake all derived from a single escaped specimen. A 1960 photo of an Aesculapian Snake supplied by Robert Jackson, a well known reptile dealer and the founder of the Welsh Mountain Zoo, depicts an Aesculapian Snake of good size suggesting that maybe the original escapee that formed the wild population of Aesculapian Snakes in Wales might have been larger than those Aesculapian Snake specimens now found around Colwyn Bay today.

3ft sub-adult / young adult female Aesculapian Snake, found on the north bank of Regents Canal, 30th April 2023

These elegant snakes range in colour from light golden-brown to dark brown with white flecks and a creamy yellow underside. Aesculapian Snakes have unkeeled scales that are very smooth to the touch, and this snake can have a very shiny appearance with an iridescent sheen in bright sunlight. The overall appearance of the London Aesculapian Snakes is often compared to that of a Twix wrapper.

Adult female Aesculapian Snake, Regent's Canal, London, 2016

Ulike all the other snake species found in Britain, it is the male Aesculapian Snake that is usually longer than the female. The female tends to have greater girth but the male tends to be longer. The female pictured above had a total body-length of just 3.5ft. A male specimen with equivalent girth would probably have been 5ft+ in length.

Adult female Aesculapian Snake, Regent's Canal, London

This adult female specimen at London exhibits several scars along her body. These may have been caused by attempted predation by birds, foxes, domestic cats, or by defensive rodents and some snakes have suffered as a result of encounters with local council workers or groundsmen using strimmers to cut the grass. Groundsmen workers at ZSL bear witness to Magpies being seen attacking these snakes on several occasions.

Adult female Aesculapian Snake, Regent's Canal, London

Will Atkins spent many years photographing and recording individual specimens of the Aesculapian Snake population in London from the summer of 2007 right up until around 2019. His photographic database allows him to identify individual snake specimens by studying unique scale markings on the head of each snake. This close-up shot of the snake's head shows the smooth un-keeled scales of the adult female Aesculapian Snake, which was identified from Will Atkin's database as snake number 15 of the London population.

This individual snake has been recorded on both sides of the canal. Whether it uses the footbridges or whether it swims across the canal is uncertain as these snakes have been filmed by members of the public on and adjacent to the footbridges. In 2011 I spoke to the owner of a canal-boat moored along Regent's Canal in 2011 who told me had had once seen a 6ft snake swimming in the middle of the Regent's Canal. Despite this species often being found in the vicinity of fresh water in Europe the Aesculapian Snake, unlike the Grass Snake, is not a species that is known to readily take to water unnecessarily, but does on rare occasion. LINK. In other European countries, such as France, where the Aesculapian Snake is considered native, the typical range for a male specimen is around 1.14ha, however males have been known to travel distances of 2km in search of females during the mating season. Likewise females can travel similar distances in search of suitable egg-laying sites too. Early results in June & August 2021, from the ongoing radio-tagging of Aesculapian Snakes in Wales by Tom Major, has shown that these snakes move about a great deal. Those specimens being monitored in Wales are proving to spend a lot of time in, under and around buildings, where they're hunting for rodents.

For reference see page 3 here: LINK

Adult male Aesculapian Snake at Regents Canal, London, 24th May 2012.

Juvenile Aesculapians are usually pale yellow, with several rows of dark brown spots. They usually display a yellow collar behind their head, making them easy to confuse with juvenile Grass Snakes. However Juvenile Aesculapians can lack the dark collar that is nearly always adjacent to the yellow collar found on Grass Snakes. This yellow collar fades and then disappears as the Aesculapian Snake reaches maturity, unlike Grass Snakes which usually retain this yellow collar throughout most of their life, especially males. Juvenile Aesculapian Snakes also usually have a black mark behind the eye that runs to the neck. After their first winter the young juvenile Aesculapian Snakes quickly take on the adult colouration, but they retain the black eye-stripe for some time.

Like Grass Snakes the Aesculapian Snake is an egg-laying snake and adult females usually produce clutches of 5-20 eggs with 5-11 being common. These eggs are grooved and can be as large as a hen's eggs.

The eggs hatch after 6-10 weeks, depending on the weather and incubation temperatures. Aesculapian Snake hatchlings are slightly larger than that of a Grass Snake, usually measuring around 15-20cm in length. The hatchlings can vary in size though and have been recorded ranging from 12-37cm in length in Europe.

In London gravid females have been seen in mid-July and the same specimens have been seen again during the first week of August already having given birth. This puts egg-laying for Aesculapian Snakes in London at the end of July, which is the same as in Continental Europe where the Aesculapian Snakes are considered native.

Adult male Aesculapian Snake, at Regents Canal, London, May 2012.

Slithering along the branches of this tree, the Aesculapian Snake is a very competent climber. They use their strong prehensile tail to grasp a firm grip when climbing or when being handled.

Adult male Aesculapian Snake with a total length of 4 ft 5 inches, including tail. Regents Canal, London 2012.

The London Aesculapian Snake is not as timid as our native Grass Snake and can often be approached for photographs without disturbing it or causing it to flee. They rely heavily on their excellent camouflage and will often remain completely motionless until they are sure that they've been seen. Although usually a shy and secretive species, due to the high levels of human traffic that pass by the London Aesculapian Snakes everyday some specimens have become pretty fearless of human contact.

There have been several occasions when these snakes have been spotted and filmed crossing both busy pathways and the canal bridges in the middle of the day when there are plenty of people about. There have been three videos posted on-line during 2019 and 2020 of an adult female Aesculapian Snake using a bridge over Regents Canal. It is possible that these are all videos of the same individual snake that has deemed it safer or easier to cross the canal via the bridge, even with people about, than risk crossing the busy canal by water.

VIDEO 1 (23rd April 2019) - VIDEO 2 - VIDEO 3

Adult male Aesculapian Snake (Snake 27 on Will Atkins records), at Regents Canal, London. 11th July 2011.

The snake pictured above was one of two specimens photographed high above the ground, basking in the canopy of a large bush at London in 2011. Aesculapian Snakes prefer slightly warmer temperatures to our native snakes and Aesculapians have been observed most often when temperatures have been between 16 - 25 degrees C, with 20-24 degrees being the favoured range.

Adult female Aesculapian Snake (Snake 7 on Will Atkins records), at Regents Canal, London. 11th July 2011.

The second of two specimens photographed high above the ground basking in the canopy of a large bush at Regent's Canal, London in 2011.

Adult female Aesculapian Snake (Snake 7 on Will Atkins records), at Regents Canal, London. 11th July 2011.

In their native countries Zamenis longissimus is considered a generalist predator but this species displays an ontogenetic shift in diet. Neonates and juveniles feed mainly on lizards and juvenile rodents. Occasionally they will also feed on amphibians and invertebrates too. Adult Zamenis longissimus feed almost entirely on small mammals, including mice, voles, shrews and rats, but these non-venomous constrictor snakes have also been known to eat lizards, small birds and eggs if necessary.

Like most snakes the Aesculapian Snake sheds its skin periodically in one complete slough. Apart from a noticeable dulling in colour and pattern, one obvious indication that a snake is due to slough is the clouding over and bluing of the scale covering the eye of the snake as pictured above. This eye-scale will sometimes shed first, and then the rest of the snake's skin will usually shed a few days later as a complete slough.

Do Aesculapian Snakes bite?

Aesculapian Snakes vary in temperament, but they are usually a fairly calm species. Many specimens do not bite even when handled. Some specimens do hiss and strike when handled but this is often with a closed mouth to serve as a warning. Others may make a strike and bite without attempting to inflict any real harm, just to get you to release them. It is reported that sometimes Aesculapian Snakes will inflate themselves in a threat display but this is not something I have witnessed myself. Other specimens can be very defensive though and will quickly bite if handled. I have found female specimens to be more likely to bite if handled, particularly in hot weather.

I must stress that there is no chance of being bitten by one of these snakes unless you try and pick one up! They will always flee rather than confront a human.

The bite marks shown in the both images above were inflicted by defensive adult female Aesculapian Snakes. This account is by an amateur herpetologist who picked up a wild Aesculapian Snake along Regents Canal in 2016:

"I spotted a large adult female Aesculapian Snake on the canal's edge, mosaic-basking amidst grass and dead twigs on the ground. Only a few inches of the scales on the middle of the snake's upper body were visible, as the rest of the snake was buried beneath the protection of the surrounding foliage. When I carefully picked up the snake to photograph the head for identification purposes, to my complete surprise, an angry, wide-mouthed head quickly spun round and latched onto my wrist. Having never experienced any signs of real aggression from Aesculapian Snakes during previous encounters, I was very surprised by how intent this snake was in defending itself from what it perceived to be a potential predator. It wasn't just biting me, It was rotating and twisting its entire body around in my hands whilst continuing to clamp its jaw around my wrist. It really meant business! After about 10 seconds it released the grip that its jaws had on my wrist, and it immediately turned its attention to my hand and began biting again. Then released, and then bit again! Then released, and then bit again!

It took me a while to realise that this snake, although drawing blood with every bite, was incapable of inflicting any real harm or pain on me. It had extremely sharp little teeth but lacked the sufficient clamping power in its jaws or the necessary tooth size to do me any real damage. After a few minutes, the snake also came to the same conclusion, and once it also realised that I wasn't actually a threat or causing it any harm it began to calm down. After a while it became quite docile and was content to slither around or just relax in my hands and enjoy the warmth for a while before being released back to the exact spot where it was found."

Although considered completely harmless many colubrid snakes have very slight traces of very mild venom in their saliva produced by the Duvernoy's gland. Studies on Garter Snakes have shown that this mild venom could aid subduing mammalian prey when the snake grasps and holds the prey in its jaws for several minutes. Even though Aesculapian Snakes have tiny teeth, and are incapable of causing any real harm or pain to humans, the small puncture wounds can cause quite a reasonable amount of blood to flow from the wound making it appear to be far worse than the superficial scratch that it actually is. Jonathan Cranfield, of Herpetologic, has commented that this "suggests that there are anticoagulant enzymes at work" from the Aesculapian Snake's saliva.

Read the paper by W & F Hayes here.

These Aesculapian Snakes living in London have made the news headlines many times over recent years but May 2014 saw a series of disgraceful reports by the British media about the Aesculapian Snake colonies found in the UK. These sensationalised and scaremongering stories were full of false information and inaccurate reports with ridiculous claims and headlines including the Daily Star's "KILLER snakes that are capable of crushing small children to death are on the loose in Britain! " the Daily Mail's "London hit by outbreak of invasive eight foot snakes that could kill cats or small dogs!" and the Metro's "Army of 6ft 6in snakes capable of killing young children on the loose in London"

Daily Star Daily Mail The Mirror (amended) UK News Yahoo International Business Times Travel AOL Metro Hackney Gazette

Less dramatic reports from these news websites:

Camden New Journal London Live The Islington Tribune Express Independant Daily Post Vice (excellent article)

Being classed as a non-native species are the Aesculapian Snakes likely to be removed?

Despite these snakes posing very little, if any threat, to our native wildlife (excluding mice and young rats) in 2013 the Government agency 'LISI' (London Invasive Species Initiative) decided that these Aesculapian Snakes were a species of concern and called for the snakes to be eradicated in the UK, quoting them as a "Species of high impact or concern". You can download the list of "Species of concern in London". Thankfully LISI didn't rush in to eradicate these snakes and in 2014 it seemed they must have listened to experts who highlighted the low risk these snakes represented to native species. LISI responded to the sensationalized media stories run by the press at the time and released the following statement alleviating any unnecessary fears and stating that they had no immediate plans to remove these snakes from the wild, at least until further studies of their impact on native wildlife have been carried out. However as of 2023 ZSL have shown no interest in allowing formal studies of these snakes with the grounds of London Zoo, and Natural England have refused to grant any licences to study the Asesculapian Snakes in London.

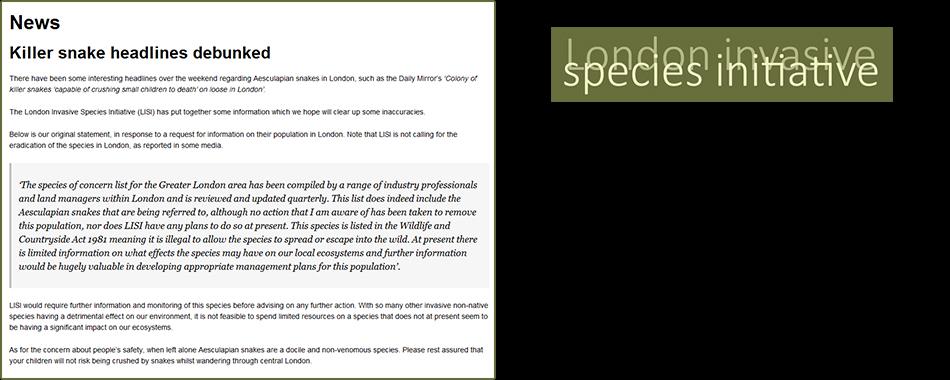

Killer snake headlines debunked

"There have been some interesting headlines over the weekend regarding Aesculapian snakes in London, such as the Daily Mirror’s ‘Colony of killer snakes ‘capable of crushing small children to death’ on loose in London’.

The London Invasive Species Initiative (LISI) has put together some information which we hope will clear up some inaccuracies. Below is our original statement, in response to a request for information on their population in London. Note that LISI is not calling for the eradication of the species in London, as reported in some media.

'The species of concern list for the Greater London area has been compiled by a range of industry professionals and land managers within London and is reviewed and updated quarterly. This list does indeed include the Aesculapian snakes that are being referred to, although no action that I am aware of has been taken to remove this population, nor does LISI have any plans to do so at present. This species is listed in the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 meaning it is illegal to allow the species to spread or escape into the wild. At present there is limited information on what effects the species may have on our local ecosystems and further information would be hugely valuable in developing appropriate management plans for this population’.

LISI would require further information and monitoring of this species before advising on any further action. With so many other invasive non-native species having a detrimental effect on our environment, it is not feasible to spend limited resources on a species that does not at present seem to be having a significant impact on our ecosystems.

As for the concern about people’s safety, when left alone Aesculapian snakes are a docile and non-venomous species. Please rest assured that your children will not risk being crushed by snakes whilst wandering through central London."

So what does the future hold for the London Aesculapian Snakes?

With many people incorrectly pointing the finger at ZSL being responsible for the escape of the original Aesculapian Snakes that founded the London snake population, in 2016 rather than attempting to remove the snakes from Regents Canal, based purely on my own observations, the action that appeared to have been taken was to lay high numbers of rodenticide bait traps in the areas that these snakes were known to use as feeding grounds. By reducing the available prey for the snakes it would have made it far harder for them to survive. It's also highly likely that some snakes have been killed as a result of secondary poisoning after feeding on poisoned rodents at Regent's Canal. In May 2020 I was emailed after a member of the public found a dead adult Aesculapian Snake at Regents Canal. The dead snake showed no signs of injury and is quite likely to have died as a result of secondary poisoning. This reinforces my views that at least part of the blame for the dramatic reduction of Aesculapian Snakes at Regents Canal is likely to be due to these rodenticide bait traps used by ZSL. Bangor University have obtained a licence permitting the capture and re-release of the non-native Aesculapian Snakes found around the Welsh Mountain Zoo, as part of their ongoing studies of this species. Sadly ZSL have never been interested in applying for such a licence and Aesculapian Snakes, found within ZSL grounds by ZSL staff over the years, have often been captured and either euthanised or taken into captivity. ZSL have within their collection some dead and preserved Aesculapian Snake specimens that were once caught within their grounds.

A quote from a member on reptile pet forum in 2018

Some Aesculapian Snakes from Regents Canal have also suffered at the hands of selfish collectors and in 2018 I witnessed members on reptile forums boasting of their intent to catch and keep wild specimens from the London Aesculapian Snake population. ZSL staff have also caught members of the public catching feral Aesculapian Snakes within the grounds of their zoo.

From 2016 to 2019 Aesculapian Snake numbers seemed to have fallen significantly. This is probably due largely to a lack of breeding success, as a result of the short supply of suitable rotting vegetation heaps, or manure piles, that are needed for egg incubation by this species. As well as some specimens being collected by reptile breeders it is also very possible that some specimens may have been deliberately killed by ignorant people who fear snakes.

In 2019 the number of rodent traps being I observed in the area seemed to have been reduced slightly from when I noticed their abundance in 2016. And with no immediate action being planned to remove these snakes at present it is hoped that they will be left free from persecution and be allowed to live in peace. With so many other more harmful and invasive species, such as the Grey Squirrel, now being accepted as part of the British wildlife, it is hoped by many that these small and restricted populations of harmless snake will also be one day accepted too.

Although breeding of the London Aesculapian Snakes has obviously successfully occurred many times since the 1980's there seems to have been very limited success in recent years. Between 2011 and 2022 there have only been two recently hatched juvenile Aesculapian Snake specimens recorded in London. The first by Will Atkins in 2011, and the second recorded on May 16th 2017 by Chris-26 on iNaturalist.org. In April 2023 a very small juvenile specimen, measuring approximately 20cm, was photographed by Martin Evans, a member of the public, on the north bank of Regents Canal, indicating that successful breeding had also occurred in 2022. On 30th April 2023 I was then able to find a 28cm juvenile specimen which would have hatched in 2022.

In 2020 the habitat around the banks of Regents Canal had changed considerably over the previous 35 years, since the introduction of the Aesculapian Snakes to London. The grassy banks that once afforded the snakes plenty of basking opportunities have now been largely replaced by Sycamore, Hazel and Hawthorn, due to the lack of maintenance at the site. This lack of suitable habitat is possibly contributing to the reduction of snakes now found at Regents Canal. The snakes will be forced to either rely more basking in tree and bush canopies or bask at the edge of the woodland, where they are at far greater risk of coming into contact with members of the public. Sympathetic management to the area would not only benefit the Aesculapian Snakes but would benefit many other species of wildlife too.

With the odds stacked steeply against the future survival of the Aesculapian Snakes in London it is feared that these wonderful, harmless creatures are unlikely to have much of a future ahead of them. It saddens me greatly to believe that we will probably allow this fascinating species, that is already in decline across the world where it is considered native, to be lost from our country for good. It is highly likely that the Aesculapian Snakes may not survive for much longer than another decade in London unless there is a serious change in attitude towards the presence of these snakes by both ZSL and Government bodies responsible for wildlife conservation in the UK.

The falsely reported Bridgend colony of Aesculapian Snakes, that were originally revealed on July 1st 2020, was a site of huge interest and importance for the study of Zamenis longissimus, and for assessing the possible future of this species in the UK. It was hoped that studies of this falsely claimed snake colony could provide answers to key questions on Zamenis longissimus in the UK. Had there actually been a colony of Aesculapian Snakes there then there would have been the opportunity to learn whether these snakes could actually successfully establish a colony in Britain at a site that wasn't situated in the immediate vicinity of a zoo. As we know zoos afford these snakes with an unnaturally high concentration of rodent prey, as seen at both the Colwyn Bay and London sites.

3ft sub-adult / young adult female Aesculapian Snake, found on the north bank of Regents Canal, 30th April 2023

Aesculapian Snakes divide the community within the field of herpetology

Whether Zamenis Longissimus belongs in the UK or not has the community divided within the field of herpetology. Some "old school" herpetologists argue that because of their current non-native status under UK law these snakes do not belong in Britain and should be eradicated. Sadly this narrow-minded approach to conservation ignores all the evidence that Zamenis Longissimus is not an invasive species and poses no risk to the ecosystems where they have been introduced in Britain.

The idea of accepting an introduced species, that hasn’t occurred naturally in the UK for many thousands of years, might be a little difficult for some people to get their head around. In fact the fossilised Aesculapian Snake remains, found at the Cudmore Grove archaeological site in Essex, were also found alongside the remains of Hippopotamus, a species which could also be found occurring naturally in the UK at that time in Britain’s history. Of course reintroducing hippos back into the wild here in the UK would be ridiculous right? So why is the Aesculapian Snake any different? The hippo now only occurs naturally in countries much further south, and thousands of miles from the UK, in areas with a habitat vastly different to that of the modern UK, which it shares with a multitude of species that are not found in our country. This situation is vastly different from the Aesculapian Snake though, which is not only still found in northern France, sharing its habitat with many of the other species currently found in the UK, but until fairly recently Aesculapian Snakes could also be found living as far north as NE Denmark, which is more northerly than any point in England.

Until these naturalists and herpetologists, that are opposed to the Aesculapian Snakes, can open their minds to accepting Zamenis longissimus in the UK, we don’t stand much chance of getting through to politicians and others in positions of power here. This debate is brought up constantly, on the UK Amphibian and Reptile Groups Discussion Group on Facebook, whenever new sightings of the Aesculapian Snake are shared within the group. Some of these recent debates can be found here:

12/05/2022 21/05/2022 02/06/2022 03/06/2022 03/06/2022 03/06/2022

During one of these Facebook debates on 4/06/2022, over the Aesculapian Snakes in the UK, Colin Melsom, a former employee of London Zoo during the 1980's, claimed that he was informed at the time by ILEA staff that the snakes released at Regents Canal were collected from southern Italy and were actually Zamenis lineatus, the Italian Aesculapian Snake, rather than Zamenis longissimus. This information is incorrect. One of the obvious and distinctive features of Zamenis lineatus is the copper red, or bright orange iris, a diagnostic feature that is commonly used to distinguish it from the Aesculapian snake Zamenis longissimus. I have been photographing the London Zamenis long enough to say with absolute certainty that none of this colony have ever shown this identifying feature of a red iris, indicative of Zamenis lineatus. Zamenis lineatus also display four dark lines that run the length of its body. Whilst these lines can fade in older specimens when this occurs the colour of the snake also fades and the result is a snake far paler than Zamenis longissimus. All the snakes at Regents Canal are definitely Zamenis longissimus. LINK LINK 2

August 2019 - As part of a debate on the future of Aesculapian Snakes in the UK, held on Facebook , world renown herpetologist Dr Wolfgang Wüster made the following comments in support of these snakes:

"I always get a chuckle out of these discussions of introduced species and the supposed threat they pose to natives. The underlying assumption (as in so much of the UK herp conservation scene) seems to be that the status quo, with our native species in the habitats they've always occupied, is still on the menu. Sorry folks, but that is just wishful thinking. Climate change is in progress, and we are seeing more of its effects every year. And while countries sign pious pledges in Kyoto, Paris and elsewhere, a look at the global scene right now (Trump, Bolsonaro etc.) suggests that it would take an unusual degree of optimism to believe that humanity has the collective will and the structures in place to significantly reduce emissions to the levels required to prevent the worst of climate change. We are in for a rough ride.

With climate change as forecast in any of the current humans-doing-too-little-too-late scenarios, not a single global ecosystem will be unaffected. "Nature", in the sense of environments unimpacted by humans, is effectively dead. There's a word for that: the Anthropocene. We are in it, and we are running the show. And since that is where we are, I suggest we would be better off owning it and trying to make the least worst of it, than pretending it's not happening,

For biodiversity, that means that the status quo is not an option. Organisms that can swim or fly will adjust their distributions accordingly under their own steam. It's already happening. Small terrestrial organisms generally don't have that choice in our fragmented landscape. So our options are to do nothing while we pretend that we don't want to interfere with a non-existent nature, while we watch the less adaptable species disappear and Britain's biodiversity decline, without any new diversity coming in to replace what is lost, OR we can decide to manage the situation and maintain overall biodiversity, and that could include welcoming non-native central European species that will now come under pressure in the southern parts of their distributions. The Aesculapian snake (as well as wall and green lizards and other Central European species) are perfect examples of that. They already interact with the same species as our natives in their current native range (so that chances of a disastrous impact are minimal even if they were to spread), and they are likely to end up having a hard time in parts of their native ranges. Why not welcome them here?

.

Note that I am ABSOLUTELY NOT advocating a free-for-all! We don't want introduced bullfrogs, corn snakes, Russian ratsnakes, red-eared sliders or other species from the other side of the world to proliferate here. But species from neighbouring regions that would get here anyway but for the Channel? I really think we need to rethink our attitudes there, and take into account the bigger picture of where we are headed." - Dr Wolfgang Wüster

On Friday the 3rd June 2022, as part of the Queen's Jubilee celebrations, the end-of-week bank holiday afforded many people the opportunity to get out and enjoy the sunshine of a beautiful summer's day. I myself took the opportunity to visit Regents Canal and headed off to once again photograph the introduced colony of Aesculapian Snakes at Camden, in NW London. With a forecast temperature of 21 degrees, little to no wind, and a bright sky with around 50% cloud cover, the conditions seemed perfect for finding this usually illusive species. On the preceding days there had already been two Aesculapian Snake sightings at Regents Canal by members of the public, who shared photos of the snakes on Facebook, so I had high hopes of success finding these snakes on our visit this time.

In recent years one of the most reliable places to find these snakes has been amongst the vegetation that grows just beneath the old aviary in London Zoo. Since the closure of this aviary a couple of years ago the enclosure has stood empty whilst major rebuilding work has taken place to transform the site into a monkey enclosure. The Aesculapian Snakes could previously often be found here basking at the edge of the tow-path, just inches away from joggers, dog-walkers and other members of the public, who formed an almost constant stream of human traffic, that passed along the busy tow-path throughout the day. When disturbed the Aesculapian Snakes basking beneath the wall would slowly slither along the base of the wall and disappear up the drainage outlets, that ran from somewhere beneath the aviary down to the tow-path. I have long suspected that whatever lay at the end of these drainage outlets within the zoo gave the snakes somewhere to take refuge, and possibly even somewhere to incubate their eggs and hibernate. In the past it is believed these snakes have used the foundations beneath heated buildings, within the grounds of the zoo, to incubate their eggs, and in 2010 several recently hatched snakes were found in the basement of a ZSL building.

Upon my arrival at the canal the first thing I noticed this time was the total lack of any vegetation beneath the old aviary wall. This area had now been completely cleared and tarmacked over, and no longer provided any safe place for the snakes to bask. I also observed that the previous drainage outlets from the aviary, that were once the size of half a house brick, had now been replaced with far narrower, tubular outlet pipes, that are now probably far too narrow for the snakes to use. These two recent changes may be a major contributing factor to the observations that followed.

As I continued walking west along the tow-path it took me just seconds to spot my first snake, a large and stocky specimen, which I estimate to be around 4.5ft in length. The snake was laying in a straight line at the base of the wall with most of its body exposed to both the sun, and to the eyes of passing people. As I knelt down and began to video record the snake it started to slowly slither in an easterly direction along the wall. It moved with no sense of urgency at all. It then slithered up the 3ft wall, with total ease, before slipping through the bars of the railings that separated the tow-path from the grounds of London Zoo. Once it had reached the top of the wall I immediately noticed another Aesculapian Snake that was coiled up just within the grounds of ZSL, only about 12 inches from the railings. The first snake joined the second snake, where they coiled up together, basking completely openly, for the duration of about 2-3 hours. At this point I was joined by my friend, and fellow amateur herpetologist, David Jones, and his partner Rochelle. I remained watching the two Aesculapian Snakes for some time whilst I took photos and video footage of their behaviour. One of the snakes remained largely motionless, whilst the other snake continued to rub its body over that of its partner, and moved up and down its length, continuously flicking its tongue against the other snake. This was clearly a mating couple. I don't know if this was part of a courting ritual, prior to mating, or if copulation had already taken place and the male was now safe-guarding the female until she laid her eggs.

After a while we decided to walk further along the canal to see if we could find any other Snakes. After walking the length of the canal, with no further success, we returned to the first pair of snakes and I continued my attempts to photograph them through the bars. My photography was attracting quite a lot of attention from members of the public that were passing by, and when I finally took my head away from the camera I realised that we had drawn quite a crowd. Video recording of the snakes became increasingly difficult for me as the jostling crowd of curious tourists tried to capture video footage and photos of the snakes for themselves. I found myself bombarded with questions about these snakes, from members of the public that were keen to know what species they were, whether they were venomous or not, how the snakes came to be found living wild at the edge of the canal, and even if the snakes could kill their pet dog!

As I took my photos I could hear David calling for my attention. He had found another pair of snakes, just a few metres along from the first pair. His calling became more persistent as he alerted me to a fifth snake in the same area, and then a sixth snake! Determined to capture some nice shots of the first snakes, it took me a while to head over to see the other snakes David had just found. When I checked for myself I saw two snakes basking separately, that were partially obscured from my camera by low vegetation. I failed to arrive in time to witness snakes 5 and 6, that were both on the move when David and Rochelle first saw them.

It didn't take long before snakes 3 and 4 also began to disperse, and they slithered off slowly in different directions from each other. Whilst one snake headed north into vegetation, and further into the grounds of ZSL, the other snake came right up to the railings, to the delight of everyone now watching these snakes. This snake showed absolutely no fear of humans whatsoever as it slithered along the top of the small wall that formed the boundary between the tow-path and London Zoo. The snake seemed to be looking for rodents as it began investigating any holes or cracks in the surface of the soil within ZSL's grounds. I remained with this snake as it made its way along the wall and the pathway just inside the zoo. David and Rochelle headed a little further east along the tow-path, where they had two further sightings of Aesculapian Snakes that were also slithering around the wall. We believe that one of these snakes was a different specimen to the six we had already seen that day, bringing our total count to seven Aesculapian Snakes for the day.

Despite the large number of people now using the pathway, as members of the public enjoyed the midday sun, two of the Aesculapian Snakes slithered down from the top of the wall, on separate occasions, and begun to investigate the vegetation beneath the wall. Again these snakes behaved in a manor that suggested they were completely oblivious to human presence, and despite the crowds of people with cameras, that surrounded the snakes, they remained completely unperturbed as they went about their business. At one point we feared for the safety of one of these snakes that was now out in the open on the tow-path, and dangerously exposed to an approaching Jack Russell dog, which was being walked by its owner along the tow-path, unrestrained with no lead. Thankfully, after some encouragement, the vulnerable snake headed back to the top of the wall, behind the safety of the railings. This snake was happy to cross pathways, and open ground, and didn't appear to be the least bit concerned about being so exposed and vulnerable. It's a little concerning that these snakes are displaying quite an unnatural level of confidence lately, and I fear that if ever these snakes were ever captured and relocated to another site then it's highly likely they would quickly perish because of their total lack of fear from either humans or predators.

Our visit to Regents Canal lasted until around 3pm, when we decided to stop looking for snakes and go for refreshments. During the five hours of our stay there was no point of the day when at least one specimen of the Aesculapian Snakes couldn't be seen either basking, or slithering along the north bank of the canal.

So with all the recent sightings does this mean that Aesculapian Snake numbers at Regents Canal are once again back on the increase? Whilst the CV-19 lockdowns of 2020 & 2021 probably helped these snakes to thrive along the usually busy canal banks, it's unlikely that this could have caused the recent boom in sightings at Regents Canal. All the snakes that have been recorded in recent years have been adult specimens, confirming that they were already present at the site before COVID arrived in the UK. So what other explanation could there be for the large number of snakes seen so far in 2022? Following the recent demolition of the old aviary, and the building of the new monkey enclosure, at ZSL, it is highly likely that the Aesculapian Snakes have been disturbed. If these snakes were, as I believe is the case, using the drainage tunnels beneath the old aviary as a place of sanctuary then the recent work may have displaced them. This is of great concern if the snakes were also using this retreat as a hibernacular during the cold winter months. The arrival of the next winter at the end of this year could prove highly perilous for these snakes if they are unable to find a suitable alternative to the site they have been using within the grounds of the zoo until now.

Regular sightings of the Aesculapian Snakes at Regents Canal during June 2022 attracted the attention of the media once again. This time it was "My London" that wrote a brief article on the snakes. The article was refreshingly written from a positive perspective. - LINK

Is it possible some of the London Aesculapian Snakes did originate from London Zoo?

There is an interesting piece written on pages 181-182, in the book "Wild Animals in Captivity" by the late A.D.Bartlett, the superintendent of Regents Park Zoo during the late 1800's. He tells of his experiences where wild-caught brown mice were introduced to snake enclosures as a source of live food. If the mice weren't caught and eaten by the snakes fairly quickly, then the mice would gnaw their way out of the enclosures, leaving a rodent-sized hole for the snake to also escape from. The practice of feeding these wild-caught live brown mice was stopped once the mistake was recognised, but not before a highly venomous cobra had escaped. Luckily this cobra was eaten by another snake in the adjoining enclosure. But A.D.Bartlett also recalls:"Years after the old reptile house had been disused, harmless snakes that had escaped in this way were found in the mill-room underneath the old house. They had doubtless lived upon the rats and mice that swarmed in this place."

The full book is available to view on-line here: Wild Animals in Captivity - by A.D.Bartlett

With this information available it's easy to see how someone might question whether there is an unlikely possibility that maybe some of the specimens of Aesculapian Snake still found along Regents Canal could indeed have originated from escapees from ZSL?

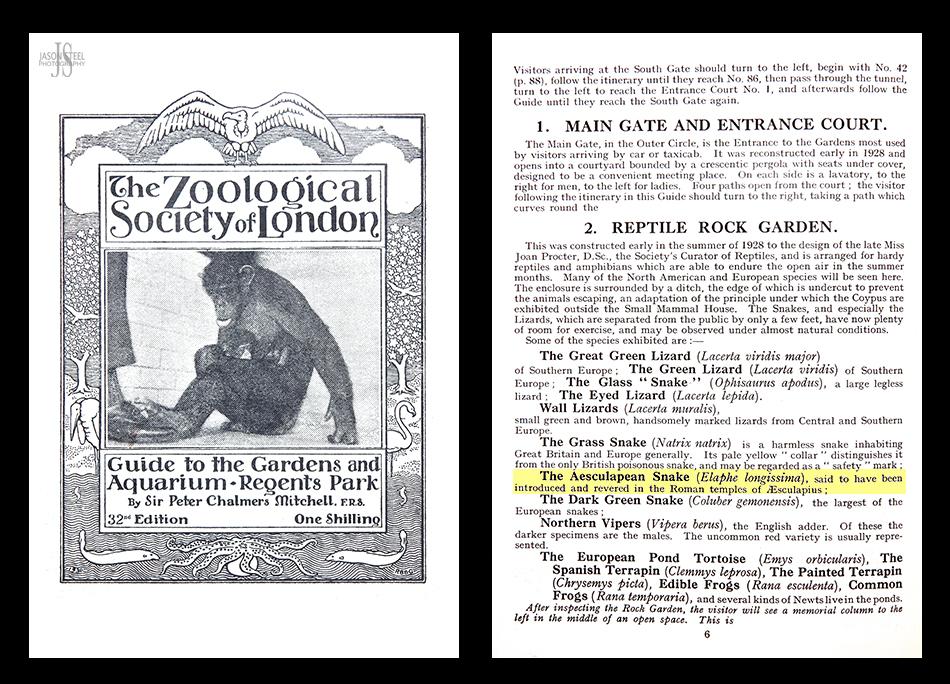

Despite some claims that ZSL never kept Aesculapian Snakes at their zoo, page 6 of the 32nd Edition, Zoological Society of London guide book dating back to 1935 (as seen below) confirms that Aesculapian Snakes were indeed one of several species of European snake kept at London Zoo in an "outdoor reptile rock garden". Aesculapian Snakes were also listed as a species kept at London Zoo on page 5 of the 1928 26th Edition of the ZSL guide book and the 30th Edition as well. These guide books confirm that the Aesculapian Snake was kept at ZSL at the very least between 1928 - 1935.

The Zoological Society of London's Reptile Rock Garden was built in 1928 and London Zoo continued to stock this outdoor reptiliary with British and European snakes until the early 1960s. It's not clear from these guidebooks how many of those years saw Aesculapian Snakes held in captivity at London Zoo. In the 1954 ZSL guide book, and subsequent guide books that followed, the Aesculapian Snake was no longer specifically mentioned as a species kept at ZSL.

Whilst it is widely accepted that the London colony of Aesculapian Snakes became established in the mid 1980's following the deliberate release of several specimens from the former ILEA building, within the ZSL grounds, there are some unsubstantiated rumours, from ex-London Zoo employees, that these snakes were already found at Regents Canal prior to this release by ILEA. Some people have even claimed that these snakes have been in existence in the area since the 1960's, or even earlier, following their escape from ZSL's outdoor reptiliary. I must stress that there is no evidence to suggest that there is any truth to these stories though, and with the possible legal implications, if they were to be true, it's unlikely that the truth would ever be revealed.

1935 32nd Edition, Zoological Society of London guide book

Britain was once part of the natural range of the Aesculapian Snake.

Fossil remains of Aesculapian Snakes found in Suffolk & Essex

In the UK archaeologists have discovered ancient fossilised remains of Aesculapian Snake at three separate sites, located in both Suffolk and Essex (B.H.S. Bulletin no.50 1994). Fossils at all three sites date back to around the time of the warm end of the Hoxnian stage or the Chibanian stage, during the Late-Middle Pleistocene Period, which ended around 126,000 years ago. - LINK

So although currently considered a non-indigenous species scientists have now accepted that Britain was once part of the natural range of the Aesculapian Snake, when the climate was slightly warmer than it is now, before being driven south by the arrival of subsequent glacial periods. This topic is covered in the 1998 book "Pleistocene Amphibians and Reptiles in Britain and Europe" by Professor J. Alan Holman. Dating of ancient fossils, and DNA analysis of living specimens, has confirmed that the isolated Aesculapian Snake populations in Northern Europe are proof that the range of the Aesculapian Snake has regularly expanded and contracted slowly over long periods of time, when necessary to cope with changes in climate, as the Earth has warmed and cooled. See articles here: 1) Relics Of The Europe's Warm Past - Phylogeography Of The Aesculapian Snake 2) Isolated populations of Zamenis longissimus (Reptilia: Squamata) above the northern limit of the continuous range in Europe.

There remains several isolated populations of Aesculapian Snake, found at sites across Europe today, which are relics of the previous vast range of the Aesculapian Snake, from just 5000 years ago when the climate was warmer than it is today. - See article here: 2005 Action Plan for the Conservation of the Aesculapian Snake (Zamenis longissimus) in Europe - by David Bird & Paul Edgar

Fossilised remains of Aesculapian Snakes have been found in the UK at these three archaeological sites:

1) East Farm, Barnham, near Thetford, in Suffolk (discovered in 1994) - LINK

2) Beeches Pit, West Stow, Suffolk (TL798719 discovered in 1991)

3) Cudmore Grove, Essex (discovered in 1990).

The British Herpetological Society Bulletin No.50 Winter 1994

In 1998 a book was published by Nick Ashton, of the British Museum, and others involved with the excavation work at the Barnham site, the author went into great detail about the history of, and the finds at, the East Farm site in Barnham, Suffolk: "Excavations at the Lower Palaeolithic Site at East Farm, Barnham, Suffolk 1989-94.- British Museum Occasional Paper 125.". In this book it was revealed that the fossilised remains found at the Barnham site were widely accepted to date back to "OIS 11, between 364 and 427 ka BP". The "OIS" are marine oxygen-isotope stages, or oxygen isotope stages, and are alternating warm and cool periods in the Earth's paleoclimate. The abbreviation "BP" means before present date. This dates the Zamenis longissimus fossils at the Barnham site to between 362,000 and 425,000 years BC, or approximately 364,000 and 427,000 years before now. Other dating methods used to date the fossils from the Barham site in 1998 indicated a minimum age of 300,000 years before present. During this warm inter-glacial period the land-mass of the UK was still joined to mainland Europe, and the Aesculapian Snake, and many other wildlife species, would have been able to expand and contract their natural range as the rising and cooling temperatures of the Earth dictated. - LINK

One might consider the possibility that these UK fossils are the remains of ancient feral populations of Aesculapian Snake, that either escaped from captivity or were deliberately released, as it is often reported that both the Greeks and the Romans kept Aesculapian Snakes in their temples for healing and fertility rituals. However, the Mycenaean civilisation of early Greece (1600BC - 1100BC) never made direct contact with Britain and the Romans did not come to Britain until 43AD, so if the fossils are dated correctly then this hypothesis can easily be ruled out as these fossils date back way further than either of these times.

Purchase "Pleistocene Amphibians and Reptiles in Britain and Europe" by Professor J. Alan Holman.

The Aesculapian Snake is an ancient species of Old World Rat Snake. It is believed that the Aesculapian Snake first appeared on the Earth as far back as 3.2 - 4.9 Mya (3,200,000 and 4,900,000 years ago), based on fossil records from Poland. - LINK

The range of the Aesculapian Snake once stretched as far north as NE Denmark, which is further north than any of he Aesculapian Snake populations now found in both Wales and England. In fact the previously native Zamenis Longissimus colony in NE Denmark was further north than Edinburgh! Until around 6500 BC mainland Britain was joined by land to the European mainland allowing Aesculapian Snakes to travel north and extend their range as necessary when the climate warmed up. So why wouldn't this species have also once been resident in the UK as well?

Whilst Britain focuses its conservation efforts and reintroduction programs on other species, including the Sand Lizard, Natterjack Toad and Pool Frog, at sites across the UK, why are we not doing more to protect the well established and naturalized populations of Aesculapian Snake in the UK? And worse still why are government agencies even considering their deliberate eradication if this species was previously found in Britain anyway, and is not only critically endangered in much of its native range across Europe, but is currently also spreading its range further north once again as our climate warms?

Should these current introduced British populations of Aesculapian Snake therefore, whether intentionally released or accidentally escaped, now be considered as a reintroduction success story of a lost reptile species now returned to Britain once again? With many specimens of the London population of Aesculapian Snakes having already been poisoned, or captured and taken from the wild by reptile collectors, isn’t it about time this species was afforded the same level of protection by UK law as our other rare herpetofauna?

The fossilised remains of Aesculapian Snake that were found at the Cudmore Grove site in Essex, were one of 14 species of herptile found there. Seven of these species are no longer present in Britain but can still be found in Continental Europe. This further supports the evidence of a once warmer climate in Britain, more suited to Aesculapian Snakes and other herpetofauna. With so many other reptile and amphibian species also being found at the Cudmore Grove site this also supports the evidence that Aesculapian Snakes were one of many species of native reptiles and amphibians that could be found living in the area at that time rather than Aesculapian Snakes being an introduced species from captive specimens brought in from ancient Greek or Roman settlements. In fact all three sites where Aesculapian Snake fossils have been found in the UK also contained fossilised evidence of other species of herptiles that are now only found in Continental Europe. LINK

Although the fossilised remains of Zamenis Longissimus can confirm that this species was once living naturally in the UK, as part of its extended range, palaeoherpetologists are not able to tell exactly when the last of this species died out here. As the last glacial period, the Devensian, started to take hold of Britain, around 33,00 years ago, our reptile species were pushed south as the temperatures dropped. Although most of south-east England would not have been covered in ice this part of England would still have been under periglacial conditions, which were highly unsuitable for species such as Zamenis Longissimus. As the warmer temperatures arrived the current Holocene interglacial phase was initiated, around 11,500 years ago, Britain started to rapidly warm again, and those reptile species that had retreated south, and had managed to cling on and endure the glacial period, were then able to spread north and recolonise areas that were previously frozen. It is not known when the last colonies of Aesculapian Snake were found in the UK but if Zamenis Longissimus were found in the UK, as recently as the previous interglacial period, then they did not survive the drop in temperatures and were clearly unable to recover their previous range after the last glacial period. Those Zamenis Longissimus found in France, that had retreated south during the glacial period, were now only able to spread north as far as the English Channel and their extended range that once ran into England was now lost forever. LINK

On 21st May 2022 the palaeoherpetologist, Mike Boyd, wrote in the ARG-UK Facebook group: "What I can say is that the occasionally-quoted date of 10,000 radiocarbon years ( = 11,700 'real' or solar years) ago is certainly incorrect. That is the date of the end of the Pleistocene Period and hence of the end of the Last (Devensian) Glacial Stage. Any Aesculapian Snakes living in Britain during the preceding Last (Ipswichian) Interglacial would have been 'pushed' southward as the ice-sheets of the Devensian Glaciation (whose maximum was between 24,000 and 18,000 years ago) advanced and eventually reached a line running from the Wash to South Wales. Most of south-east England would not have been ice-covered but would have been under periglacial conditions. I cannot imagine Z. longissimus surviving. So the species probably last became extinct in Britain some 20,000+ years ago. I say "last" because there is fossil evidence of Aesculapian Snakes recolonising Britain in earlier Interglacials and (we may assume) becoming extinct here in the alternating Glacial periods."

It is my hope that one day Natural England, and our Government, will no longer consider the Aesculapian Snake to be a non-native, and potentially invasive, species but instead will embrace it as a returned species once native to the UK and afford it the same level of protection under UK Law that our other rare reptiles benefit from.

Does this mean that we should reintroduce all species that were once found in the UK? No, definitely not. Other species that were once found in the UK would no longer integrate into Britain’s current ecosystems without disrupting their delicate balance. In the UK the Aesculapian Snake has found its place in two current ecosystems, where it can both thrive and fully integrate in harmony with its surroundings. If Aesculapian Snakes were to become widely established once again in Britain they would not become an apex predator but would simply become another piece of the food-chain for local ecosystems. Having Aesculapian Snakes in areas inhabited by humans can actually be a benefit to man as they would serve as a beneficial response to counteract the increase in mice and rats that are now often found in abundance around human habitation, which is a direct result of man’s behaviour. Due to the lack of suitable Aesculapian Snake habitat in the UK it would be highly unlikely that this species could ever become common in the UK once again. However it could, if allowed, form healthy colonies at certain sites across the UK, where there are ideal conditions.

The Aesculapian Snake even features on Wikipedia's list of "Extinct Animals of the British Isles".

Sadly as the current UK Law stands any species that wasn't present in Britain after the end of the last glacial period, around 11,500 years ago, and hasn't subsequently arrived here of its own accord, without accidental or deliberate intervention from humans, is considered to be a non-native species. Although this is bad news for the Aesculapian Snake in the UK it does open the door to the possibility of licenced reintroductions of Moor Frog, Pool Frog, Agile Frog and European Pond Turtle at some stage in the future. All of which were once found native in the UK well after the end of the last glacial period.

This map shows the range in 2020 for Aesculapian Snakes across Europe. See detailed ICUN Red List map here. See also European Environment Agency Map