St Denis' Church, East Hatley, Cambridgeshire, 9th September 2022

Bournet's Cave Spiders at St Denis' Church, at East Hatley, Cambridgeshire

In

2006 a small colony of the nationally scarce Meta

bourneti were

at risk of being left homeless when an old air-raid shelter, where

they were discovered in Papworth Everard,

Cambridge,

was scheduled to be demolished to make way for development.

Thankfully a rescue and relocation plan was put into action by Rob

Mungovan, who at the time was the Ecology Officer at South Cambs

District Council.

The Cave Spiders were transferred to an underground room, beneath St

Denis' Church, some 11 miles away in East Hatley. The

identity of these large orb-weavers

was officially confirmed, by microscopic examination, in the summer of 2006 as Meta

bourneti

by Brian

Eversham, entomologist and pervious CEO of the Beds, Cambs and Northants Wildlife

Trust. Despite

the "nationally scarce" status of Meta

bourneti

there are actually more records of the rare Meta

bourneti in

Cambridgeshire than there are for the far more common European Cave

Spider, Meta

menardi. Since the 2006 discovery of the Cave Spider colony in Papworth Everard there were numerous further sightings of Cave Spiders being discovered in many different dark locations in Cambridgeshire. These included a Gamlingay WWII bunker, drains at Madingley Cemetery and even phone equipment boxes in Arrington. Although proving far more numerous than previously expected none of the other sightings were officially examined and identified to a species level unfortunately.

At

the time of the transfer St Denis' Church was a local, disused,

medieval church in the small, rural village of East Hatley, Cambridgeshire.

Beneath the Grade II* listed building lay a disused furnace chamber

that would provide an ideal hideaway, for these dark-loving spiders,

where they could continue their existence undisturbed. St Denis' Church was situated in a small local nature reserve and it seemed the ideal location to be used as a receptor site for such a relocation. These rare spiders would share the church with other scarce species, including Brown Long-eared Bats, Plecotus auritus, that roost in the building, and Great Crested Newts, Triturus cristatus, that spend some of their terrestrial life in the church's cellar. The tiny

furnace chamber is a dark, damp, underground storage room with

limestone walls and a clay covered floor. With no windows in the

furnace chamber there is no light entering this underground room, and

here the spiders are very rarely ever disturbed by human visitors.

Hidden away from the rest of the world the Bournet's Cave Spiders

have managed to thrive since their introduction, and successful

breeding takes place yearly.

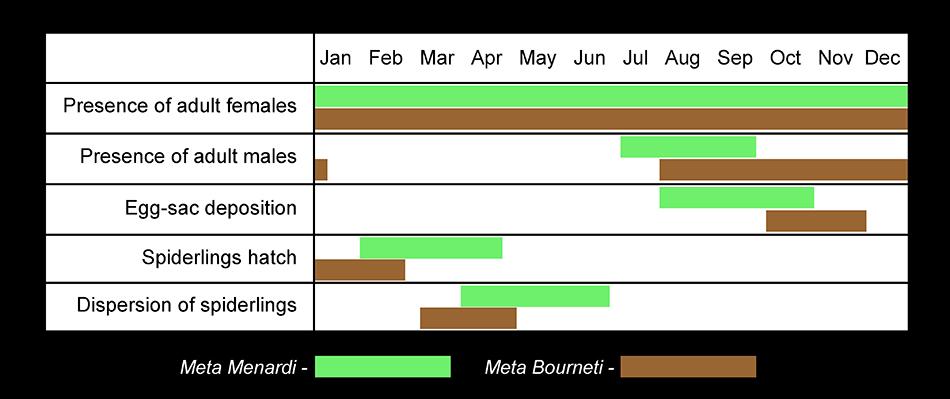

On 9th September 2022 I was given the privilege of surveying and photographing these special spiders. The idyllic old church is situated on the grounds of a small nature reserve. The old wooden door at the entrance to the furnace chamber remains locked to the public, but proudly displays a notice informing visitors of the presence of Cave Spiders beneath the church. I chose autumn for my visit in the hope of finding female Bournet's Cave Spiders guarding their egg-sacs. Thankfully the timing was perfect and I wasn't disappointed. On this visit I was able to record 5 adult male specimens, 11 adult female specimens, and 1 sub-adult specimen. I counted a total of 14 egg-sacs, however, only 5 of these egg-sacs had females guarding them so at least some of the others may have been old egg-sacs. The large, white egg-sacs were suspended from the top of the damp walls and had a diameter of around 20-25mm, each resembling small, hairy table-tennis balls. Two of the adult females were in very close proximity with male specimens, which were likely to be their mating partners or potential suitors.

Due to their largely sedentary nature these spiders typically remained fairly motionless even when exposed to the dimmed light of my studio photography lamp, or even the very bright light from my diffused camera flash unit. Some of the females guarding their egg-sacs began to nervously scuttle around the egg-sac as I approached closely with my camera. One female specimen hid behind her egg-sac when my lens got too close. Using a twig I gently lifted the egg-sac to reveal the hiding spider. To my utter surprise the spider then jumped from the egg-sac and landed on my camera, before slipping off and falling to the ground, about 20 inches below. The spider then walked back to the wall, where its egg-sac was suspended, and slowly began to ascend the wall towards the egg-sac once again. However, the spider never actually returned to the egg-sac whilst I was there watching. It's still not clear whether the spider's jump towards my camera was an attempt to flee or maybe to defend the egg-sac?

I was keen to photograph an adult female specimen on a white background so I chose to capture a lone specimen, that was easily accessible, and wasn't guarding an egg-sac, or partnered with a male. The large female specimen I selected didn't have a particularly swollen abdomen, so either it hadn't mated yet, or it had already produced an egg-sac that it wasn't guarding. As I placed the spider on my white sheet of plastic it was noticeably uncomfortable as its legs failed to grip to the slippery surface. It took a few minutes of escape attempts before the spider finally settled down and remained motionless for a brief moment. This pause allowed me the opportunity to capture my photos. During its escape attempts I used my hand to block its escape routes several times, and at no time did the spider exhibit any defensive behaviour other than to run away. After a few minutes I'd captured the images that I was after, and the spider was placed gently back to the exact same spot on the low ceiling where it was found. Once back in place the spider continued to remain motionless, exactly as it was before its capture.

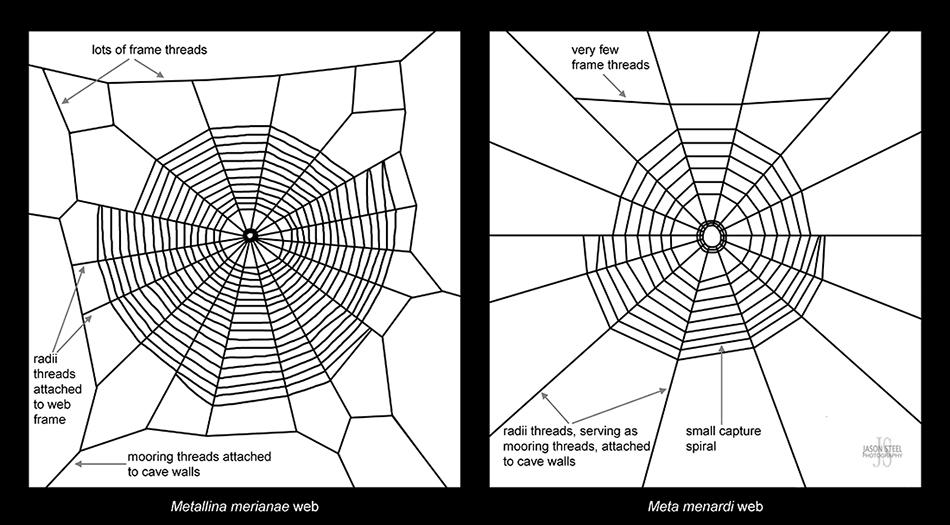

The tiny furnace chamber of St Denis' Church has probably reached its maximum carrying capacity for this species. Although adult Cave Spiders are photophobic, and choose habitats of total darkness, the newly emerged spiderlings are attracted to light and the majority of these will leave the furnace chamber and head off in search of new territories to colonise. One adult specimen has been found under a manhole cover at a nearby residential property, so these spiders can be found in suitable locations in the area that surrounds the church. The only sub-adult specimen that was found on my visit to the church's furnace chamber had built its web on the archway leading into the chamber, and was the closest specimen to the exiting door.

Within the webs of the Cave Spiders I found the remains of Cellar Spiders, Pholcus phalangioides, as well as a small slug, several woodlice and one Violet Ground Beetle, Carabus violaceus. Their were also mosquitoes on the walls that would provide a light meal for the spiders given the chance. The Cave Spiders are not the only predators living under the church. The furnace chamber is also shared with Cellar Spiders, Pholcus phalangioides, that were slightly more numerous than the Meta bourneti. 19 Pholcus phalangioides specimens were recorded on my visit. Pholcus phalangioides are known spider hunters, and whilst I found evidence that Meta bourneti were feeding on young Pholcus phalangioides, it is highly likely that this is reciprocated with Pholcus phalangioides feeding on the young Meta bourneti too.

* Grateful thanks to Peter Mann for allowing me the opportunity to photograph these Meta Bourneti, and thanks to Rob Mungovan for information on the history of this colony. *