14mm female Purse-web Spider (Atypus affinis), on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

Purse-web Spider (Atypus affinis)

The Purse-web Spider is a nationally scarce, illusive and very distinctive spider in the UK. This special spider is our only native species of mygalomorph. Mygalomorphae is a sub-order of arachnids that includes Tarantulas, Trap-door Spiders and Funnel-web Spiders. All other spiders found in Britain are of the sub-order Araneomorphae. The Purse-web Spider is most frequently found in the south of England, with a very scattered distribution at other coastal and heathland sites around the UK. The preferred habitat is heathland and undisturbed grassland sites, especially chalk or limestone grassland.

The Purse-web Spider has relatively short legs and a small abdomen, compared to its large cephalothorax, and huge chelicera and fangs. When viewed from above the chelicera can be longer than the cephalothorax itself. Despite the spider's intimidating appearance their bite is not dangerous to humans. Whilst the large jaws are capable of inflicting a fairly deep bite the venom of the Purse-Web Spider is harmless to humans. Males usually reach a body-length of around 7-10mm and the larger females 10-15mm. 22mm female specimens have been recorded in the UK. Males can be identified by their darker scutum in the anterior half of their abdomen. Males also have a slightly smaller abdomen and longer, thinner legs than the females. The legs of the male are also darker with light tarsi. The legs of the female are fairly universal in colour and they're slightly lighter than those of the male. The female's legs can also look slightly translucent. Typical habitat can include heathland, chalk grassland, and even road-side verges. They also seem to have a preference for south-facing slopes.

The Purse-web Spider spends most of its life living underground in a silk-lined tunnel. This tunnel extends above ground in the form of a 4-10cm sock-shaped purse web. This sock-web resembles a wooded root and is often fixed to short grass or low vegetation via tough silk at the surface end. The spider often covers this part of its web in leaves and other debris, making it very difficult to spot. The Purse-Web Spider waits hidden inside this purse / sock web for unsuspecting invertebrates to walk over the surface of, or land on top of, the sock. At this point the Purse-web Spider springs into action and using its hugely over-sized fangs it bites through the webbing and into its prey from underneath. The prey is held in place until sufficiently subdued, before the Purse-Web Spider drags the prey back down through the web. Sometimes the spider has to cut a slit in the sock-web before its prey can be dragged through. Underneath each of the spider's impressive chelicerae is a row of 11 or 12 very sharp teeth. When the prey is pierced by the spider's fangs the spider then pulls the prey downwards, impaling it against these sharp teeth. These rows of small teeth are also used as a saw to cut a slit in the surface of the sock so that prey can be dragged into the burrow.

Atypus affinis often dispose of their dead prey above the ground near the sock part of their web. From examining these remains Atypus affinis is known to feed on beetles, earwigs, flies, woodlice, and bees. It's very likely that the Atypus affinis would probably feed on any crawling invertebrates that happen to stumble across its web.

The burrow of the Purse-web Spider usually extends to depths of 15-30cm below the surface of the ground, but can sometimes be as deep as 50cm. Adult females usually spend their entire lives below ground living in their burrows. Adult males do leave their burrows for one purpose though, usually in late summer or early autumn, as they head off in search of female burrows in order to find a mate. Males can sometimes also be found searching for females in the springtime. Male Purse-Web Spiders are attracted to the burrows of mature female specimens by a scent released by the females. Upon arrival at the burrow of a potential mate the male will begin strumming and tugging on the webbing. As with many species of spider this pattern of strumming and tugging will be unique to this species and will be easily recognisable by a female so there's little chance of her confusing this male with a potential prey species. If the female isn’t receptive to his approaches she will tug back aggressively on the webbing and the male will retreat and continue with his search for a mate.

Once the male Purse-Web Spider enters the burrow of a receptive female here it will remain for the rest of its days. The male dies shortly after mating, usually at the age of 4 years old. The male does not even live long enough to see its offspring hatch. The female and her offspring will feed on the dead body of the male, although they play no part in his demise. The female lives for around 8 years in total.

When mating occurs in autumn the female egg-sacs will not hatch until the following summer. Juvenile specimens usually continue to live with their mother in her burrow for close to a year. After this they can be found above ground as they disperse from their mother's burrow and head out looking for suitable habitat to build burrows of their own. The spiderlings may not always immediately build a burrow of their own but may spend the first stage of their independent life living above ground for a while. On heathland sites in Surrey groups of tiny Purse-web Spiders have been photographed building a communal silk rigging in heather, before dispersing. LINK

It is believed that the Purse-web Spider hibernates at the bottom of its burrow during the colder months of November through to February.

Even in the depths of its burrow the Purse-web Spider has one enemy, the Spider-Hunting Wasp, Aporus unicolor, which specializes in preying on Atypus affinis, and hunts the spider in its own burrow. Once located the wasp uses its sting to paralyse the spider before injecting it with its own eggs. The wasp larvae will hatch and feed on the paralysed spider. Due to the rarity of the Purse-web Spider this wasp is also a nationally scarce species. On heathland sites the Purse-web Spider often builds its burrow at the sloping edge of pathways, or bare patches of sand, under overhanging heather.

There there are 3 species of Atypus found in Europe, Atypus piceus, Atypus muralis, and Atypus affinis. There is some speculation though that Atypus piceus could just be the result of hybridisation between Atypus affinis and Atypus muralis. Atypus affinis is the only Atypus sp. found in the UK.

The Purse-web Spider is actively hunted by the parasitic wasp Aporus unicolor. This is a specialist spider-hunting wasp that specifically seeks out the rare Purse-web Spider in its habitat. Once the wasp invades discovers the purse-web it invades the web and then paralyzes the Purse-web Spider with its sting. Once paralyzed the wasp then lays a single parasitic egg in the spider. As the grub of the wasp grows the spider dies. The grub then feeds on its remains. Being such a specialist predator of a scarce species is goes without saying that Aporus unicolor is also a nationally scarce species. - LINK

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

Whilst this most might look aggressive the spider is merely putting on a threat display as a warning not to be messed with. As I laid on the forest floor photographing this Purse-Web Spider I tickled its chelicerae with a blade of grass to encourage it to show its fangs. Once the fangs were reared up as a warning the spider held this pose for about 10 minutes without making any attempt to strike. As with many other mygalomorphs the Purse-Web Spider has flashes of red colouration beneath its chelicerae that add to the dramatic effect of the pose and serve to intimidate any potential attackers.

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

14mm female Purse-web Spider, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

24cm extracted Purse-web, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

The image above is the full sock-web of the Purse-Web Spider after it had been extracted from the loose sandy soil of a path-side bank at a Surrey heathland site.

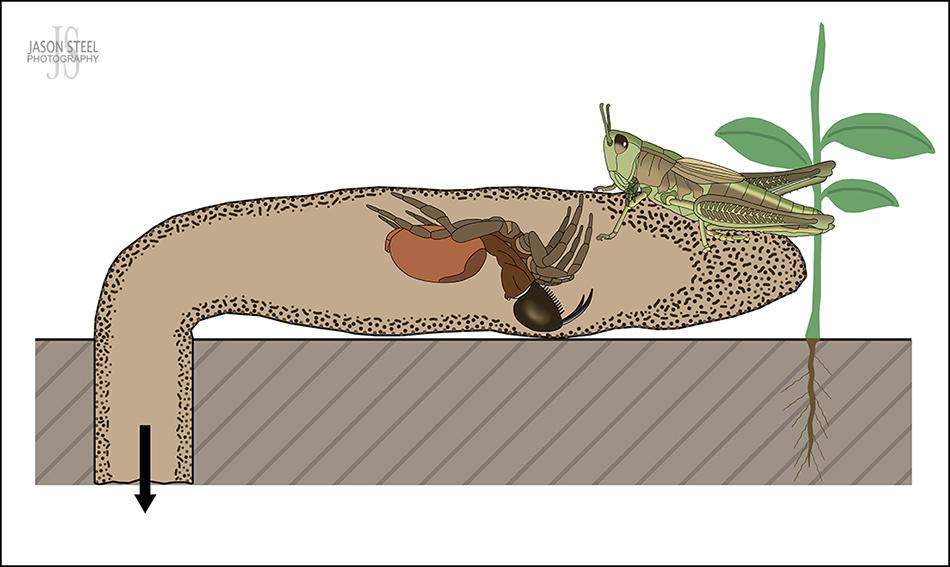

Purse-web Spider, illustration by Jason Steel

This illustration depicts an unsuspecting grasshopper walking over the surface of the purse-web. Using its huge fangs the Purse-Web Spider would quickly bite through the surface of the purse-web and pierce the soft underbody of the Grasshopper. The fangs would draw the Grasshopper down against the small sharp teeth of the Purse-web Spider, where it would be pinned until the venom took effect. Once subdued the motionless Grasshopper would be dragged down through an opening in the purse-web, cut by the spider's small sharp teeth. The Grasshopper would then be taken down into the depths of the burrow. Once the prey had been consumed, or wrapped for later consumption, the Purse-Web Spider would return to the upper section of its burrow to repair the damage and seal the purse-web once again.

This digital illustration was loosely inspired by a drawing from the 1958 "World Of Spiders" book, by W S Bristowe. I sketched pencil drawings from my own photographs first before creating the final illustration in Photoshop.

3 of the 5 Purse-webs recorded on Surrey heathland, 9th October 2022

These small sections of the Purse-Webs, measuring just 4-6cm in length, disguised the true length of the burrows, which probably extended to 20-30cm or more beneath the surface of the soil.

14mm female Purse-web Spider on the palm of my hand.

Tiny 2.5mm Purse-Web Spiderling extracted from a subterranean Purse-web, on Surrey heathland, 1st October 2022

Despite their tiny size the 2.5mm spiderlings are perfect miniature replicas of the adult Purse-Web Spiders. The spiderlings can emerge from their purse-web anytime from February onwards if the weather is mild enough. Most mygalomorph spiderlings disperse by walking, but Atypus affinis is different. Atypus affinis spiderlings disperse by ballooning, a method of dispersal adopted by many "true spiders". They exit the purse-web for the first time, and do so in mass. They then climb to the top of nearby vegetation. Here they construct a network of communal webbing, whilst they wait for perfect conditions to disperse. When the conditions are right the spiderlings release a long strand of of silk which allows them to fly in the air like a kite. They then release the strand and allow themselves to be carried away by the air currents. This enables them to disperse over far greater distances than would otherwise be possible by just walking. When they land they begin looking for suitable substrate to dig their new burrows. From here onwards their lives will be entirely subterranean, apart from adult males, which will leave the burrow once they reach maturity and are ready to search for a female mating partner.

This behaviour was photographed on Surrey heathland in 2020, by photographer Dom Greves - LINK, and in February 2023, by Nopeland Discovery, in north Somerset. - LINK

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

How did I capture these photos of a female Purse-Web Spider?

Until October 1st 2022 I had searched in vain for Purse-Web Spiders to photograph for several years. The adult female Purse-Web Spider spends its entire life beneath the ground, hidden away in the safety of its burrow. Most female Purse-Web Spiders rarely see daylight during their adult life. Mature male specimens can occasionally be found though if you're lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time. Usually in the autumn, but occasionally in the spring, mature male Purse-Web Spiders leave their burrows and head off above ground to search for the burrows of female Purse-Web Spiders, in the hope of finding a mate.

Over the last couple of years I had tried visiting known hot-spots for Atypus affinis, in the hope of encountering a wandering male Purse-Web Spider, with no success at all. In October 2022 I headed to a heathland site in Surrey, where I had previously photographed several of the other species of wildlife that are featured on my website. On arrival at the site the weather was warm and dry with an air temperature of around 17 degrees. The sky had about 70% cloud cover with regular short bursts of sunlight, and even though I wasn't aware of any previous records of Atypus affinis being found at this site the habitat looked ideal and my hopes of finding a wandering male Purse-Web Spider were fairly high. After a few hours of searching the site I had failed to find any Purse-Web Spiders above the ground and my hopes had started to fade. I then decided to switch my focus to looking for the hidden webs of the Purse-Web Spider instead.

Before the day began I had pensively pondered over the moral dilemma of what I would do I were lucky enough to find the burrow of a Purse-Web Spider? Whilst I love my wildlife photography with real passion I have always carefully considered the well being and benefits to any species that my photography would affect. Was it right to potentially destroy the burrow of a nationally scarce species just so I could obtain my photos? This question troubled me for some time and I decided that I would only attempt to remove a burrow if I confidently felt that I could safely do so without causing irreversible damage to either the burrow or the spider itself. I also resolved that I would be using any photos obtained to educate and raise awareness of this threatened species. I then considered what time of year that would be least destructive to disrupt the burrows. My initial thoughts were that if the males could be found out searching for females during the autumn then surely this would be the best time of year to avoid disturbing a burrow that had the risk of containing either an egg-sac or young spiderlings inside? As it turned out I was wrong, and a little more research on the subject would have revealed that the spiderlings can be found in burrows for most of the year and usually start to disperse during the spring. In truth there is no ideal time to dig up these burrows.

So on this beautiful autumnal day I began my search by meticulously checking the south-facing banks of the sandy footpaths, that ran through the heathland, for signs of the small section of Purse-Web, that's situated above the ground, leading to the subterranean burrow of the Purse-Web Spider beneath.

After a long and painstaking search on my hands and knees I eventually found what I believed to be the 'sock' of the Purse-Web Spider. At just 4.5cm in length this section of the sock was smaller than I had expected to see, and I wasn't convinced that this was indeed what I was looking for. I pulled out my small garden trowel and very carefully began to loosen the soil around the sock. The sandy soil was already very soft and loose and it took minimal effort to delicately prize the full length of sock out from the ground. Yet again the full length of this sock was shorter than I had been expecting at just 12cm in length. It was with eager anticipation that I ran my fingers along the length of the sock to check if its creator was still resident inside. Sadly though this sock was completely empty, so it was then placed back in the ground from where it was removed.

I had previously read that where one Purse-Web is found there are usually more nearby, so I continued to search through the surface of the soil in the immediate vicinity. And there within a 60cm radius of the location of my first Purse-Web I sotted a further three socks. The visible sock sections ranged from 4cm to 6cm, & 7cm in length. I chose to unearth one of the larger and the most easily accessible Purse-Webs in the hope of finding this elusive spider. It proved similarly easy to excavate the full length of the sock from the soil but this sock went far deeper that my previous discovery. Once removed the sock was measured to have a total length of 24cm. On this occasion though there was an obvious bulge at the very bottom of the sock and my heart began to race with excitement as the chance of completing my mission grew ever closer.

The sock was laid in plastic container and the tip of the sock, that was previously found above the ground, was carefully opened up. Very slowly I began to encourage the bulge, situated at the opposite end of the sock, towards the opening I had created. The bulge took several minutes to reach the opening and I held my breath as the chelicerae of a good sized female Purse-Web Spider emerged first from the sock. She was reluctant to leave her burrow and once removed she sat very still, as she took in the surroundings of the world above ground, that she probably hadn't been exposed to for several years. This spider was absolutely stunning to see! The Purse-Web Spider is so incredibly unique in appearance when compared to any other British species. However, my complete delight of finally finding this incredible spider was brought to a sudden and abrupt halt as I then discovered the adult female Purse-Web Spider had not been alone in her burrow. Behind the female Purse-Web Spider a tiny, semi-translucent spiderling came slowly trundling out of the sock. I now had a heavy heart at the realisation that I had disturbed a nest. I quickly folded over the tip of the sock to prevent further escapees from leaving the sock, and my determination was now stronger than ever to successfully return this burrow safely to the ground once I had taken my photos. The spiderlings found in the sock had a body-length of around 2.5 - 3mm, and would have hatched from the egg-sac during the summer months. At this time of year they were likely to be from 4-12 weeks of age.

The sun had now come out from behind the clouds and I decided that I'd rather photograph the Purse-Web Spider, and her spiderling, using diffused flash lighting as opposed to ambient light. I headed off to the shade of the nearby hardwood forest that grew at the edge of this heathland site. Once under the cover of large trees I set about photographing my subjects on a white sheet of plastic. Even after placing my subject on a white plastic background the adult female Purse-Web Spider remained totally motionless for about 5 minutes. I began to fear that the spider may have been harmed during my excavation. I felt considerable relief when she finally sprung to life and began trying to trundle off.

After I'd photographed the spider on a white background I then gently placed the spider on the large green root of an adjacent tree, that stretched across the forest floor. The bright green root would add a touch of contrasting colour to the images. Once again the spider stayed totally still for me. It really was proving to be the perfect photographer's model. When it did start to move it immediately headed to the bed of pine needles that littered the ground and began to try to bury itself. Having photographed and observed this adult female Purse-Web Spider it was very clear that this spider was adapted to a life beneath the ground. Above ground, with its very short legs and stocky body, the spider was slow moving and lacked the agility seen with all other terrestrial species of spider. On the surface of the forest floor this spider would be very vulnerable to attack from predators. Even though the mature males only spend a very short part of their lives above ground, as they search for the burrows of a female mate, it's noticeable how much quicker and more agile the males are with their slightly thinner and longer legs.

The spiderling behaved very differently to its mother though and it was active the entire time it was placed on the white background for photos. Being so tiny I didn't risk photographing the spiderling on a natural background for fear of losing it.

With such an accommodating subject it didn't take too long for me to capture all the photos of the Purse-Web Spider that I had hoped for. I made sure that I captured her from every angle, and on several different backgrounds, as this would be the one and only time that I would ever excavate a Purse-Web Spider's burrow. I then retuned to where the burrow of the spider was originally located. Using a suitably sized stick I began poking a hole in the soil to a depth that slightly exceeded the length of the Purse-Web Spider's sock. The diameter of the stick was also slightly larger than that of the original burrow, which allowed me to slide the full length of the sock back beneath the ground in the same spot that it was excavated from. I left the tip of the sock above the ground as it had been before. The most difficult stage of the task was encouraging the adult spider to return back into her sock. Once both the adult spider and the spiderling were back in the sock I placed a very thin covering of loose soil around edges of the sock and placed a small amount of loose heather over the top of the sock. Whilst the Purse-Web Spider has been at the very top of my "wish-list", for species I'd love to photograph, for many years, this encounter left me with a bitter sweet feeling. I'm delighted that I managed to finally capture all the photos I was after, and add this species to my website, but my conscience is slightly troubled because of the disruption I have caused to a nest of young spiderlings, that would not usually leave the burrow for many more months. I now hope that my photography session hasn't been too disturbing for these special spiders, and that the adult Purse-Web Spider will reseal the tip of her burrow, and their subterranean life beneath the ground will continue as before.

Wandering male specimens.

The males usually head off to search for the webs of female mating partners in Autumn, and sometimes in spring. This is usually the only time these magnificent spiders are ever seen above ground. The Purse-web Spider is most frequently found in the south of England, with a very scattered distribution at other coastal and heathland sites around the UK. Here are some recent records of wandering males found by members of the public:

May 11th 2023 - Studland Heath, Dorset. - LINK

November 14th 2023 - Private garden, Three Legged Cross Village, east Dorset. - LINK

November 15th 2023 - Durdle Door Beach, south Dorset. - LINK

November 19th 2023 - Croydon, south London. A very unusual record as this male specimen was found running across a dinning-room floor. - LINK

A video, filmed in Cumbria, was shared on YouTube, which showed the Purse-web Spider in ideal habitat at the most northerly extent of their range in the UK. This colony of Atypus afinis were filmed on the south-facing, sunny slopes of the South Lakes in Cumbria, where these spiders build their sock-webs under the limestone rocks that are common on these slopes. - Watch video here.

All Photographs on this page were taken using the Canon 7D mkii camera, the Canon 100mm Macro 2.8L IS lens, Canon 580 ex flash and MK Diffuser.