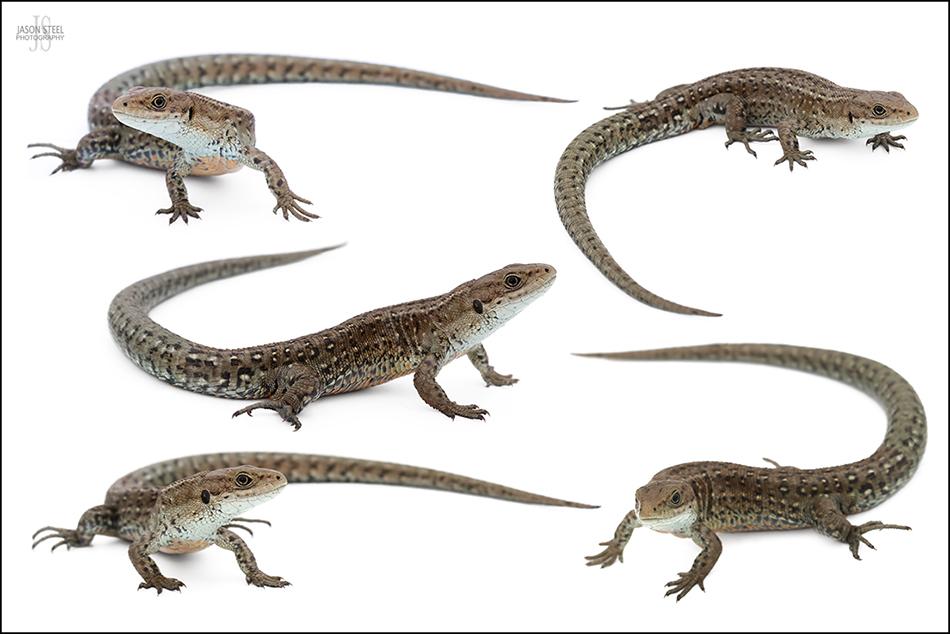

Viviparous Lizard / Common Lizard (Zootoca vivipara).

Here in the UK there are three native lizard species and a further two non-native species that have well established breeding colonies in certain parts of the UK.

Native:

The Viviparous / Common Lizard - (Zootoca vivipara)

Sand Lizard - (Lacerta agilis)

Slow Worm (leg-less lizard) - (Anguis fragilis)

Non-native:

Wall Lizard - (Podarcis muralis & possibly Podarcis sicula)

Western Green Lizard - (Lacerta bilineata)

Viviparous Lizards are fairly small reaching a maximum length of 150mm including full tail. They are notably smaller than our other native lizard the Sand Lizard.

Male Viviparous Lizards have bright orange or bright yellow undersides with many black spots. These colours are more clearly visible during the breeding season.

The female usually has a plain pale creamy-yellow coloured underside with no or very few spots. Some female specimens can have an orange underside but will not have the speckling of the males.

The most accurate way to sex the Viviparous Lizard is to look for the hemi-penal bulge present on all males at the base of the tail. Males also have larger heads and longer tails. Females tend to have longer bodies and smaller heads.

Patterning on the back of Common Lizards can also aid sexual identification, but is not always accurate. Males tend to have rows of spots and females tend to have unbroken lines running the length of their backs.

These active lizards can be found in varying shades of brown, ginger and dark green. Melanistic examples are also found across the country on occasion.

They are quite a hardy species and are usually the first and the last reptiles to be seen in the UK. I saw my first Viviparous Lizard of 2012 on January 2nd showing how quick they are to emerge from hibernation on even the mildest of days. In the wild Zootoca vivipara usually live for around 5-6 years but in captivity these lizards have been known to reach 12 years of age.

The Viviparous Lizard is the only native reptile found in Ireland and it is also the only native reptile on the Isle of Man.

The broken pattern on this male Common Lizard's tail shows that the lizard has 'dropped' its tail at some point to evade capture from a predator. The tail has re-grown well in this case. This a defence mechanism adopted by all the lizards found in the UK. When at risk from a potential predator the lizard will drop its tail as a last resort of defence. The tail will continue to thrash about, and hopefully distract the predator, so the lizard can escape. When lizards drop their tails the tails do usually slowly grow back, but never to the original length. It can also be perilous for lizards if they're forced to drop their tails towards the end of the summer, or in autumn. The tails contain vital fat reserves which the lizards are dependent on to see them through hibernation and during the winter months when food is extremely scarce. Without their tails these lizards may not survive a long winter. The tail can break off at a few specific points along the base of the tail. But each break-off point can only be used once so the lizard can only drop its tail a limited number of times to evade capture.

This cumbersome gravid female gave birth to ten young shortly after this photo was taken. It is rare for these lizards to give birth to more young than this. A clutch of 5-9 is more usually the case. The word "viviparous" means to give birth to live young that are fully developed within the adult females body prior to birth. The female Common Lizards give birth to live young. They do not lay eggs. They are born encased in a thin membrane which the young lizards quickly free themselves from.

This juvenile Viviparous Lizard is just a few days old and is already totally independent and hunting food for itself. Juveniles are usually very dark brown in colour. They tend to have an almost metallic bronze appearance.

Viviparous Lizards are quite brave and will often bask quite openly and return to the same basking spot as quickly as 10 minutes after being disturbed and scared off.

Viviparous Lizards are often found in small groups. These two juveniles have not yet developed their full adult colouration. The young lizard in the foreground of this photo has dropped it's tail to avoid being caught by a predator which was most likely a corvid or a domestic cat.

One of 23 Viviparous Lizards I recorded on this grassland site in Kent on a warm sunny morning 2014. Most were seen basking on logs, rock-piles or in the grass. A couple were found under refugia.

This dumped sheet of corrugated iron quickly absorbed the sun's rays and made an ideal basking spot for this male Viviparous Lizard.

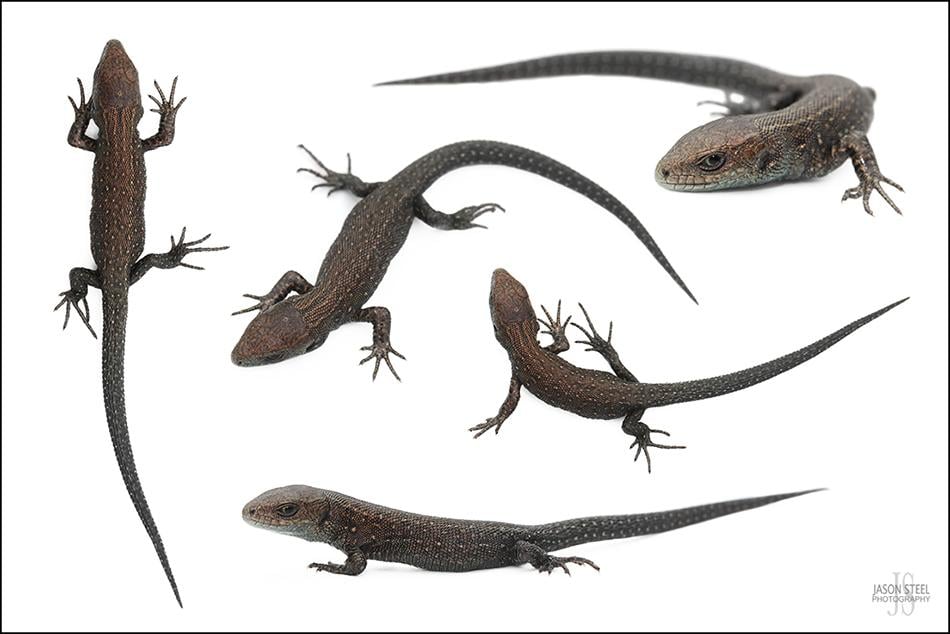

Adult female Sand Lizard, photographed in captivity under licence 2014

Sand Lizard (Lacerta agilis)

Sand Lizards are the UK's rarest native lizard and are fully protected by UK law. They are restricted to just a few places across England and can be found in Dorset, Hampshire, West Sussex and Surrey on heathland at dune sites. There is also an isolated population resident at the Lancashire coast at Sefton. This northern population varies slightly in appearance. There have recently been reintroductions of Sand Lizards at several sites including one at the Talacre Dunes in Wales as part the captive bred release programs by ARC-Trust and Chester Zoo.

Adult female Sand Lizard, photographed in captivity under licence 2014

Sand Lizards are larger and stockier than than our Common Lizards and can grow to around 20cm in length. Despite the latter part of their scientific name "agilis" these lizards are not as fast or agile as their smaller, slimmer and longer-legged cousins the Common Lizard. There are strong visual differences between male and female Sand Lizards during the mating season (April/May). The males usually have bright green markings along their flanks. Out of the mating season the two sexes are harder to tell apart. The green markings are much less obvious but males are stockier in build and have larger heads. The eye of the male sits only about a third of the way along its head (nearer the neck) but the female's eye sits about half way along the head.

Adult female Sand Lizard, photographed in captivity under licence 2014

In 2014 I had the opportunity to photograph these well-fed, captive Sand Lizards. These specimens were part of an ARC-Trust captive breeding program that allowed juvenile specimens to be reintroduced into the wild.

Adult female Sand Lizard, photographed in captivity under licence 2014

Adult female Sand Lizard, photographed in captivity under licence 2014

Adult female Sand Lizard, photographed in captivity under licence 2014

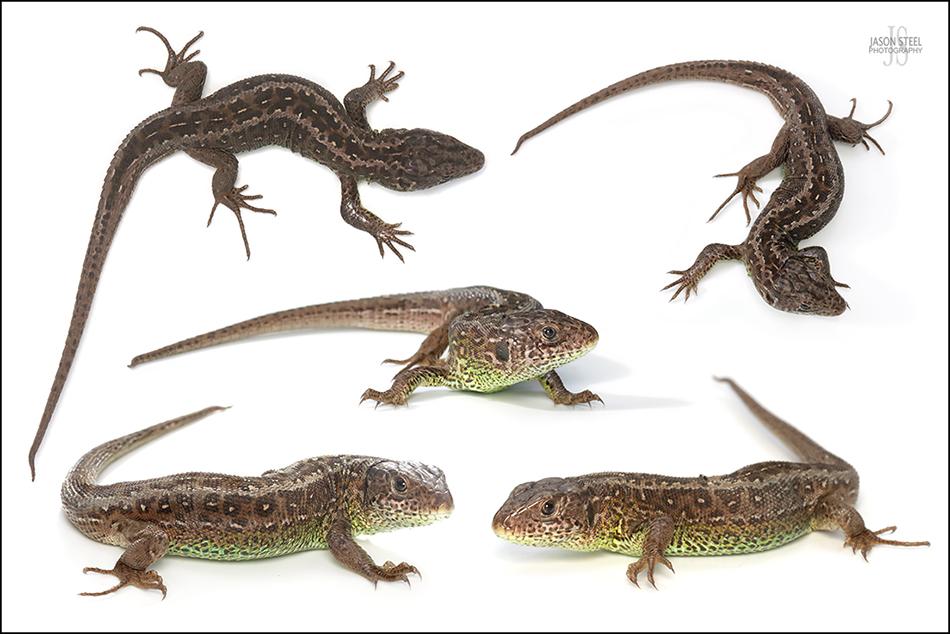

This young adult male Sand Lizard basks on a log pile built as part of the excellent land management at a heathland reptile site in Surrey. It was photographed in May 2016, when the males exhibit their mating colours with the vivid green sides of their head and body.

Juvenile Sand Lizard basking on a log in Surrey heathland, September 2014

Sand Lizard eggs are laid in clutches of 2-16 usually around end of May or the start of June. They are laid in soft sand that is exposed to the sun and they rely entirely on the warmth of the sun for them to hatch. In poor summers this may result in very few if any successfully hatching. The juveniles are left to fend for themselves and will prey on small insects. They have two long light dorsal stripes along their backs and a row of spots along their flanks and look similar to adult females. Juvenile Sand Lizards look vastly different to juvenile Common Lizards which are very dark in appearance and do not possess any of the Sand Lizards markings.

The Slow Worm - (Anguis fragilis).

Slow Worms, also known as Blind Worms, are neither slow, nor blind, nor a worm. Neither are they a snake. They are in fact the UK's only limbless lizard. In Britain Slow Worms are the most commonly encountered reptile in residential gardens. They can often be found under logs or rocks, or basking at the sunny edge of nettle beds. They are a welcome visitor to any garden, or allotment site, as theses carnivorous lizards feed on terrestrial invertebrates, especially slugs and snails. Whilst a Slow Worm may superficially look like a snake there are a few key features that instantly identify it as a lizard. Firstly, look closely at the eyes. If you stare at a Slow Worm for long enough you'll notice it blink. That's because lizards possess eyelids, which snakes do not. Secondly, if you turn it over you'll notice that the underside, or ventral side, is covered in the same tiny scales as the rest of its body. Now if you looked at the underside of a snake you'd see very different scales. On the underside of a snake you'd notice one long single row of thin, scales that reach from one side of its body to the other. Thirdly, if you look at the tongue you'll notice the tongue is relatively sort, and parallel-sided, with a triangular shaped notch at the tip. By comparison the tongue of a snake is long and forked. If you hold a Slow Worm it feels very smooth, almost like glass, and looks very shiny in the light. This is because their tiny scales don't overlap like the scales of a snake, and they lack the raised ridge, or keel, present in the centre of both Grass Snake and Adder scales. And lastly, Snakes have a distinct neck area that's slightly more narrow than the head or its body. With a Slow Worm there is no obvious neck and the width of the body appears to almost continue into the head.

Adult male Slow Worms are fairly uniform in colour and shade and tend to be slightly paler than adult females. Adult females and juveniles have dark flanks and a dark dorsal line that runs down the centre of their back.

Slow Worms typically grow to around 30-40cm in length but the largest ever found in the UK had a total body length in excess of 50cm. It was recorded and photographed on the Steep Holm Island in Somerset. The photos are publicly displayed at the visitors centre there.

Having no limbs allows the Slow Worm to move effortlessly through long grass, leaf litter and rotting vegetation. This makes hunting for slugs and earthworms in compost heaps far easier.

Slow Worms have minimal defense against predators. Firstly if caught they will defecate. The poo of the Slow Worm is similar to watery bird droppings. Slow Worms may also thrash about to cause the would be predator to lose grip of them. And lastly if all else fails they may drop their tail at will. The dropped tail will thrash about by itself and this will often distract the predator for long enough for the Slow Worm to make its escape.

Caution should always be exercised when handling Slow Worms as they may drop their tail. Never try to grab hold of the Slow Worm. Although the Slow Worm can re-grow its tail the new tale will never be as substantial as the original and the new tail is usually a much shorter stumpier replacement. The tail of the Slow Worm is an essential area for storing body fat, which Slow Worms need during long periods of hibernation. This shedding of their tails to evade capture is what gives the Slow Worm the 'fragilis' part of their Latin name 'Anguis fragilis'.

There is only one point at the base of the tail where the tail can break away. This detachment point can only be used once so the Slow Worm can only drop its tail one time during its entire lifetime. Considering how long these reptiles can live the Slow Worm cannot afford to waste this emergency escape plan due to unnecessary and careless handling by humans.

Adult male Slow Worm

In the UK we only have two native species of reptile that produce eggs, the Sand Lizard and the Grass Snake. Slow Worms, Common Lizards, Adders and Smooth Snakes all give birth to live young. The newly born Slow Worms exit the mother each encased in a thin, clear membrane, which they quickly break free from. An image can be seen here.

Young Slow Worms are born at the end of the summer, generally in August or September, in clutches of up to 25. They are light gold - bronze in colour with a dark line running down the centre of their back and dark sides. As the Slow Worms grow older the males will gradually lose these markings and their colour becomes greyer in colour. The females will retain some degree of the darker flanks and dark median line. Senior males can also display light blue spots with age. The female retains the darker sides and often has other linear markings.

Adult male Slow Worm

Slow Worms are believed to live for up to 20-30 years in the wild. The record for a Slow Worm in captivity was an amazing 54 years for a specimen kept at Copenhagen Zoo. Slow Worms are semi-fossorial (meaning burrowing) and spend much of their time hidden from view. They are best found by turning over items on the ground (usually rubbish) that attracts heat from the Sun's rays. They do sometimes bask openly (usually gravid females) and can be found in nettle patches. They are frequent visitors to compost heaps.

Adult male Slow Worm

Like most lizards and snakes Slow Worms can swim if necessary but it's very rare to see Slow Worms take to water. John Cobham captured a beautiful shot of a Slow Worm swimming and his image can be seen on Facebook here.

Aged adult male Slow Worm

As Slow Worms grow older their colour tends to fade especially with males. Occasionally old male Slow Worms can develop bright blue spots along their back.

Another ageing male Slow Worm starting to develop blue spots on its back.

Melanaistic Slow Worm

Melanism is the increase of the black pigment 'melanin' in the skin of animals. It is the opposite of albinism. All reptile species can produce melanistic examples. In some species this is considered extremely rare whilst in others it is fairly common. This partially Melanistic Slow Worm is the first I have seen and melanism in Slow Worms is considered very uncommon.

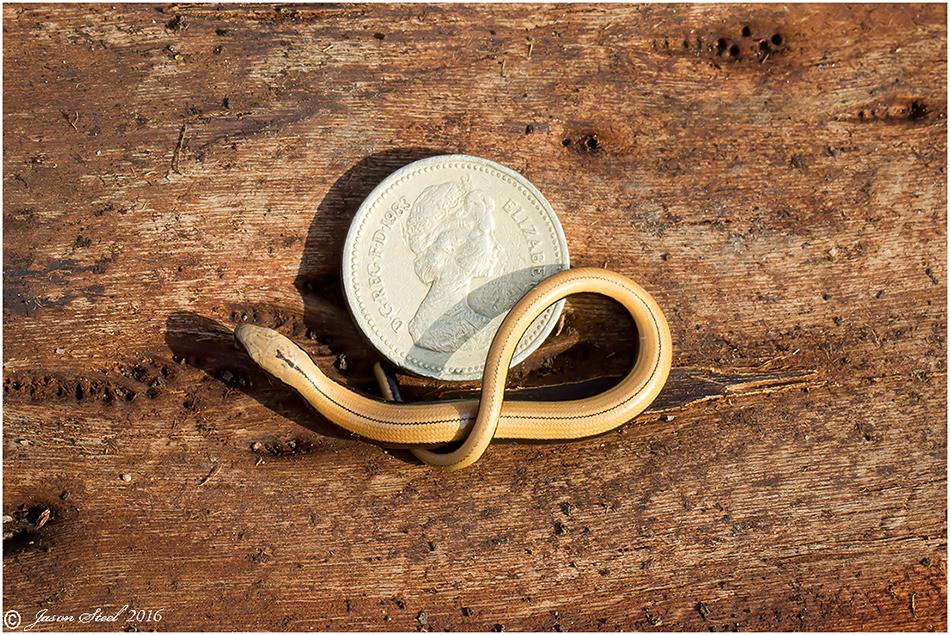

9cm juvenile Slow Worm

Juvenile Slow Worms, like the one pictured above, have dark flanks and a dark vertebral (back) stripe. These markings usually remain to some degree as female Slow Worms mature but males will lose them and become much more uniform in colour.

9cm juvenile Slow Worm

Taken in April 2016, this juvenile Slow Worm is one of last year's young and still measures just 9cm in length. The £1 coin has been placed to give an idea of scale.

Adult male Slow Worm

This adult female Slow Worm was found slithering over damp autumn leaves at the edge of dense woodland. The Slow Worm was living up to its name and was struggling to remain very active with the cool mid-October air temperature of just 11 degrees, a cloudy sky and very little sunlight.

Slow Worms have very small flat unkeeled scales giving them a very smooth shiny appearance. When newly sloughed Slow Worms can look as though they're made of glass.

Adult male Common Wall Lizard, photographed at Boscombe, Dorset 2012

Common Wall Lizard / aka European Wall Lizard - (Podarcis muralis).

The Wall Lizard is a non-indigenous species found in the UK and is thought to have originated from several deliberate and accidental introductions from Europe. They are slightly larger than the Common Lizard growing to a maximum length of 180-200mm including the long tail. They have a longer and more pointed face than the Common Lizard, and the eyes are set nearer the top of their head too. The males sometimes exhibit brightly coloured green or yellow backs. Wall Lizards can show huge variation in colour within the same colony. They have established healthy breeding colonies on a number of coastal towns across the south of England, with the largest populations being found in the Bournemouth area. There is even a colony in SE London. They have also been recorded in smaller numbers at many other sites across the UK, suggesting multiple releases via the exotic pet trade. The Wall Lizard is also found across the island of Jersey where they are native to the island and are afforded legal protection. There are also many other species of Wall Lizard, from the Podarcis genus, found across Europe too. Podarcis species can often be very difficult to identify down to species level. However, herpetologists have only encountered two known species of Wall Lizard in the UK so far, Podarcis muralis and Podarcis sicula. It is only the Common Wall Lizard, Podarcis muralis that is known to have established breeding colonies here. The Common Wall Lizard is very good at colonising new areas and is now found at many coastal sites in the south of England. Boscombe is one such site where they have been present in large numbers for many years. DNA testing on Common Wall Lizards found at UK sites has shown that we have introductions from both France and Italy, but not Spain. The Common Wall Lizard, Podarcis muralis is classed as native to the Island of Jersey, where the Common Lizard, Zootoca vivipara, does not occur.

Other known colonies in the UK include Dover, Kidbrooke Nature Reserve near Eltham, Bristol, & Shoreham Beach near Brighton.

LINK (The invasion Ecology of the Common Wall Lizard)

Adult male Common Wall Lizard, photographed at Boscombe, Dorset 2012

Females tend to lay clutches of 2-12 eggs in thick vegetation, holes in the ground or underneath rocks. The eggs usually hatch around 5-7 weeks later in July. They are thought to live for around 10 years. They can be found in very dense populations of huge numbers on any one site if the conditions are just right for them. Wall Lizards in the UK are often seen well into October before hibernating. They will often emerge in mid-winter to bask if the sun comes out for long enough and have been seen basking in both December and January on occasion. Wall Lizards are very fast-moving and highly agile and can leap to catch all manor of insect prey. They often thrash their prey once caught against rocks before swallowing it head first.

Juvenile Common Wall Lizard, photographed at Boscombe, Dorset 2013

Juvenile Wall Lizards often have the same bronze metallic appearance of the juvenile Viviparous Lizard but they are not as dark in colouration. Young Wall Lizards are prey for many species including on occasion larger Wall Lizards. One example where cannibalism has been recorded within this species at a site in Kent can be seen here: LINK

These Wall Lizards are a colourful addition to our coastal cliffs where they sometimes occupy habitats unsuitable for our own native herps. They are not so welcome at other sites though where their speed, agility and aggression makes them able to out-compete our native Sand Lizards and Viviparous Lizards. Because of this there have been other sites in the UK where Natural England have responded quickly in removing an introduced population of Wall Lizards before they've had a chance to spread beyond control. Wall Lizards are canniblistic and will feed on their own young. - LINK. Wall Lizards have also been known to feed on the young of our native lizards too, confirming that Wall Lizards are not only a competitor to our native lizard species but also a predator of them too. LINK

Some sites in the UK, that were once home to native species of lizard, have now been completely taken over by the introduced and non-native Wall Lizard. Wall Lizards also provide a valuable source of food for other predators on coastal cliffs too. I have watched Kestrels hunting lizards on the cliffs of Boscombe on more than one occasion.

Italian Wall Lizard / Ruin Lizard - (Podarcis sicula)

Apart from the Common Wall Lizard, Podarcis muralis, there is also another similar species of Wall Lizard that arrives in the UK on occasion, usually amidst imported stone, the Italian Wall Lizard, Podarcis sicula. Podarcis sicula is already established and breeding at one undisclosed site in the UK. There are also some unconfirmed claims of other possible colonies in Dorset, however these unconfirmed sightings are likely to be a case of mistaken identity for the Common Wall Lizard, Podarcis muralis. Podarcis sicula that arrive in the UK tend to quickly disperse some distance, so they are far less likely to establish breeding colonies here in the UK. Whereas Podarcis muralis tend to stay local to their introduced area for a while, a tactic far better suited to colonising foreign lands. Podarcis muralis are known to live for around 13 years in captivity. Although most sightings are of isolated specimens, as of 2023 it is possible that small colonies of Podarcis sicula may have become established at other locations across the UK now.

In 2010 Podarcis sicula were accidentally introduced to a site in Buckinghamshire following the import of a shipment of Italian stone. Natural England and ARC-Trust were quick to respond and prevent these non-native lizards from becoming established in the area. Several specimens were captured and taken into captivity. The surrounding vegetation was then cut back to discourage any further specimens from becoming established in the area. LINK

On November 3rd 2020 a sub-adult was found in Oxfordshire. LINK

On11th May 2021 a gravid female Podarcis sicula was photographed on a wall in Marske-by-the-Sea. In April 2022 there were sightings of more than one Podarcis sicula at the same site. LINK

On 23rd May 2022 an adult male Italian Wall Lizard was photographed at a garden Centre in Gravesend, in north Kent. There was another sighting at the garden centre on the 26th May 2022, this time by a staff member. The lizards occasionally arrive at this garden centre hidden, amidst imported plants from Italy. It's likely that this latest find is an isolated specimen rather than being part of an established colony in the area. Accidental imports of this species aren't that rare, but due to the quick dispersal of the Italian Wall Lizard they don't usually succeed in establishing new breeding colonies. Because of this single specimens found in the wild here in the UK are not usually considered to be of high risk, however it's important to ensure they are not breeding at sites in the UK. LINK LINK 2

The Western Green Lizard (Lacerta bilineata).

The Western Green Lizard is a very brightly coloured green lizard and is only found in the Bournemouth area of Dorset, along the south coast of England. Specimens have been recorded at Bournemouth, Boscombe and Southbourne. They are considerably longer and stockier than other lizards found in the UK growing up to 150mm long or 400mm including the tail. 130mm being the average length of an adult specimen. The males are usually more colourful and some exhibit a blue throat and lower face parts especially during the mating season in the spring. Males also have larger heads than the females. It is widely accepted that these lizards have been introduced to England following deliberate or accidental release of captive specimens from the reptile trade. It is highly likely that there have been numerous releases in the area. The earliest reports of these lizards in Bournemouth dates back as far as the 1970's but confirmation of Western Green Lizards being present wasn't until the 1990's. The average lifespan of the Western Green Lizard is around 15 years. DNA tests on the Bournemouth Western Green Lizards have confirmed that this colony originated from specimens of Slovenian origin. LINK

In 2011 these lizards were doing well in Boscombe near Bournemouth, Dorset however numbers have declined significantly recently due partly to the very poor summers and harsh winters of 2011 and 2012. Because of their beautiful appearance they have also have been victims of collectors for the reptile pet trade. Another reason for their decline is predation from a pair of resident Kestrels that have been seen searching for, and feeding on the Western Green Lizards on the cliffs. Bournemouth Borough Council promote these "exotic lizards" as a tourist attraction to the area: Bournemouth Council Website

The Western Green Lizard is also found across much of the island of Jersey especially in the SW where they have a stronghold. On Jersey these specimens are totally native to the island where they are afforded full legal protection. The Western Green Lizard has also been deliberately reintroduced to the island of Guernsey, where they are also considered to be native.

The adult females often retain the juvenile longitudinal stripes running the length of their backs and tail. Adult males lose these stripes and have more obvious blue colouration to the throat. The Western Green Lizard reaches maturity at around two years of age, by which time they are around 8cm in length, excluding their tail. Eggs are laid in batches of 6-25, usually in the warmth provided by rotting vegetation or decomposing logs.

All photos on this page were taken using the Canon 40D Camera with one of the following lenses: Canon EF 100mm f/2.8 Macro USM, Canon EF 100mm f/2.8 L Macro IS USM, Canon EF 70-300mm f/4-5.6 IS L .