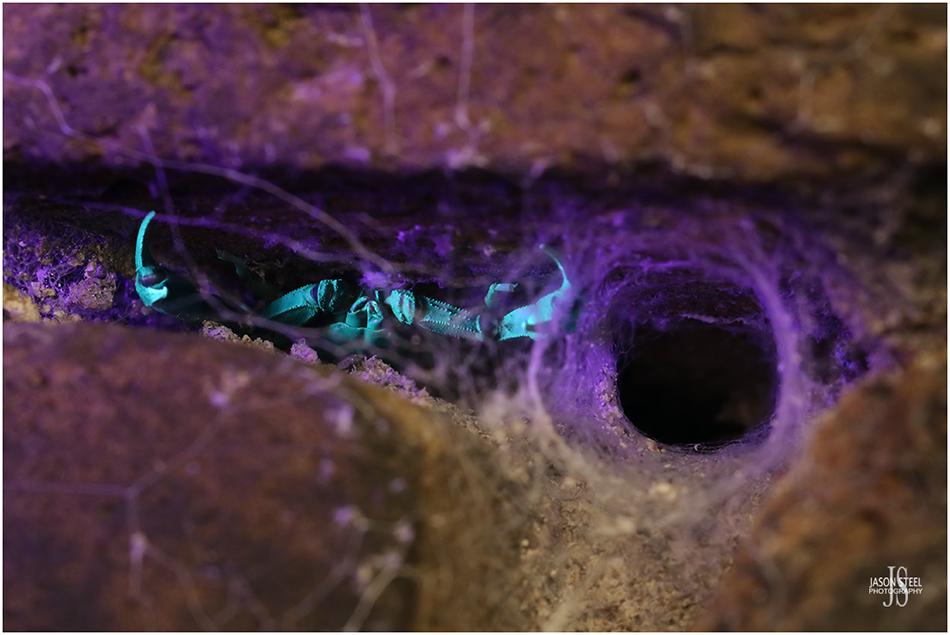

Yellow-Tailed Scorpion, Euscorpius flavicaudis, at Sheerness Docks, July 2024.

Yellow-Tailed Scorpions at Sheerness

Scorpions are the oldest known arachnids on the planet. When one thinks of scorpions its common to associate them with hot countries such as Mexico, which has the highest biodiversity of scorpions anywhere in the world, where there are approximately 200,000 envenomations per year and around 300 human deaths from scorpion stings. - LINK

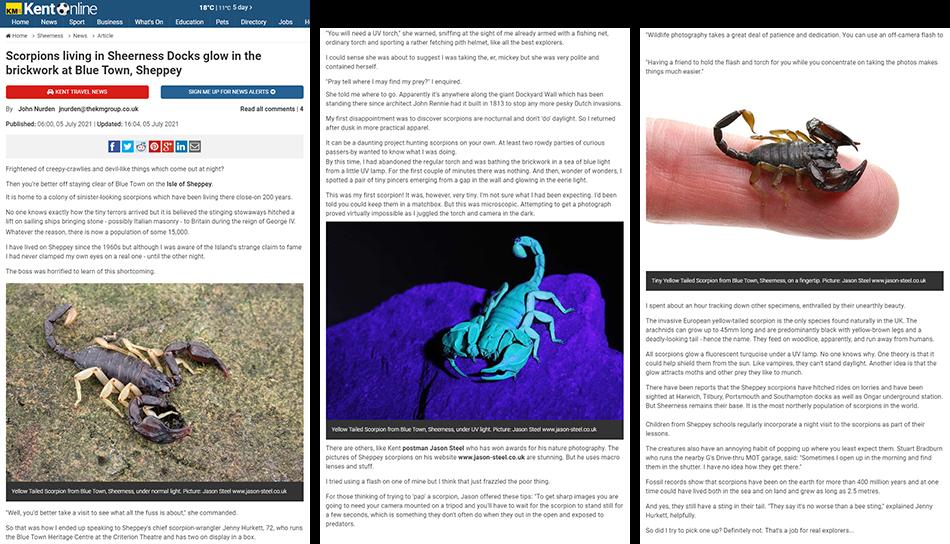

It often comes as quite a surprise to most people when they learn that we've actually had scorpions living and breeding here in the UK for over 150 years. The small Yellow-Tailed Scorpion, Euscorpius flavicaudis, has managed to establish a thriving colony, in an isolated area in SE England, despite the generally cool and mild climate here in the UK . These scorpions have been found on occasion at several coastal towns across the south of England over the years. The best known and most successful introduced population can still be found on the Isle of Sheppy, in Kent, around the dock-land town of Sheerness. This Yellow-Tailed Scorpion population was estimated in the late 1980's to consist of around 700 specimens. Due to the sedentary nature of these scorpions it has since been agreed by many arachnologists that this initial number was probably grossly underestimated. Many sources now claim that the Yellow-Tailed Scorpion colony at Sheerness could be as large as 10,000 or even 15,000 specimens. I can't find any information on how this 10,000 - 15.000 figure was ever calculated though and after studying and photographing the scorpions at Sheerness myself for the last 15 years I personally believe that the colony, whilst definitely thriving, is probably far smaller than these claimed figures.

This population was the first ever scorpion colony recorded in the UK. Old records are a little sketchy but it's believed that these scorpions first arrived at Sheerness Docks during the 1860's. The Natural History Museum has a preserved Yellow-Tailed Scorpion specimen in its collection, which was collected from within the grounds of the Sheerness Docks in 1870, and was identified at the time by J. J. Walker. This is the earliest confirmed and identified specimen so we known that these scorpions were already established at the docks before 1870. The Yellow Tailed Scorpion has been living in the south-facing walls, rock crevices, abandoned buildings and railway sleepers of these docks for over 150 years now and still thrives there today in 2024. In fact these little arachnid stowaways have been established in Britain for longer than the Grey squirrel, which didn't arrive in the UK until it was imported and deliberately introduced in 1890, during the Victorian era.

Although no one knows for sure it is widely accepted that these small scorpions originally found there way into the UK accidentally as stowaways amid the regular shipments of Italian masonry, that were brought to the docks aboard sailing ships during the reign of George III. Due to the success of this scorpion colony it's likely that it became established as a result of multiple additions from accidental stowaways over the years. The construction of the Great Dock Wall was initially finished in 1813. It's very possible that the scorpions may have been introduced to the area when the Italian masonry that was used in the building of the Great Dock Wall was imported. So although the Yellow-tailed Scorpions were not officially identified at Sheerness until 1870 it is quite possible that they arrived long before this date and had survived in the wall undetected for many years.

Euscorpius flavicaudis is sometimes referred to by its synonym, Tetratrichobothrius flavicaudis. Other sources refer to this species as Euscorpius (Tetratrichobothrius) flavicaudis . - LINK It seems there is much confusion whether Euscorpius flavicaudis was transferred from the Euscorpius genus into the Tetratrichobothrius genus, of which it is the only species. However, both names are currently still widely in use and accepted. Both names were assigned by De Geer, in 1778.

Pronounciation: Euscorpius flavicaudis (You-scorp-ee-us flav-ee-cordiss) / Tetratricobothrius flavicaudis (Tettra-tri-co-both-ree-us flav-ee-cordiss)

22mm gravid female Yellow-Tailed Scorpion at Sheerness Docks, July 2024.

Although the majority of the Sheerness scorpions live within the relative safety of the private docks some specimens can be found on the south-facing wall that surrounds the docks, which is accessible to the public. The Yellow-Tailed Scorpion is native to much of Western and Southern Europe, including France, Italy and Spain as well as Northwest Africa, where it is usually recorded at altitudes below 500m. These tiny scorpions prefer dry and humid habitats, including forests, fields and parks, but are often also found in or around human habitations as well. Like other species of scorpion the Yellow-Tailed Scorpion has two very small eyes situated on the top of the cephalothorax. Additionally scorpions also often have between 2 and 5 pairs of tiny eyes in the front corners of the cephalothorax. Whilst these eyes cannot generate a sharp image they are incredibly sensitive to variations in shades of light. These eyes allow the scorpion to navigate in extremely dark conditions. Scorpions are not entirely reliant on these eyes as their only means of sensing what is occurring around them. The body of the scorpion, especially its legs and claws, is covered in tiny sensory hairs that are able to detect the slightest of air movements or vibrations from its surroundings.

The Old Great Dockyard Wall is a Listed Structure, built around 1823, that measures up to 430cm high and is up to 66cm deep.

The Yellow-Tailed Scorpions are the most northerly species of scorpion in Europe and it is their tolerance to cold temperatures and their ability to adapt to a variety of habitats that has allowed them to become established and thrive in the UK's cooler climate at Sheerness. During the colder months these scorpions remain inactive deep within the dock wall or under rocks and railway sleepers etc. Tim Benton's studies in the late 1980's measured the internal temperature of the Old Dockyard Wall at Sheerness during the winter. It was found that the temperature in the middle of the Great Dockyard Wall would only ever drop to around 3 degrees even during the coldest spells of winter. The Yellow-Tailed Scorpion can survive temperatures at least as low as -7 degrees for relatively short periods of time, so the UK's winters are not a problem for this hardy species at Sheerness.

I have seen it written elsewhere that Euscorpius flavicaudis is the most northerly species of scorpion in the world, but this is incorrect. It is true that the Yellow-Tailed Scorpion is the most northerly scorpion species in Europe, and perhaps the most northerly scorpion outside of the Americas. But the title of "the most northerly scorpion in the world" goes to Paruroctonus boreus, a medium-sized scorpion from the family Vaejovidae, that's found in both north America and Canada. Paruroctonus boreus is commonly called the Northern Scorpion. - LINK LINK 2

No one knows exactly why the Yellow-Tailed Scorpions have managed to successfully breed and thrive at the Sheerness Docks when all other introduced populations of these scorpions have failed within a few years at other sites across the UK. It could be significant factor that the Isle of Sheppey has a relatively low mean annual rainfall of just 18 inches, compared to that of 24 inches for London and 60 inches for Devon and Cornwall? The average rainfall recorded at coastal sites across the UK is typically twice that of the average rainfall at Sheerness.

Sheerness Port was originally built in 1665 as a Royal Navy dockyard and fort, and was later rebuilt with the inclusion of the Great Dockyard Wall in 1823. The Great Dockyard Wall, along with the now ruined army barracks and various other old buildings within the docks, are all constructed using the same brickwork, that appears to be particularly favourable to the Yellow-Tailed Scorpions. This is likely to be due to the very soft mortar between the bricks, that allows the scorpions to tunnel into the wall. The huge 66cm depth of the Great Dock Wall allows the scorpions to escape the freezing temperatures of the UK during the cold winter months. Within the grounds of Sheerness Docks are gardens, allotments and areas of rough ground, which favour all manor of insect life, providing an ample and constant supply of insect prey for the Yellow-Tailed Scorpions. In addition, areas of the north face of the Great Dockyard Wall have ivy climbing the wall and overhanging trees which also provide a rich environment for insect prey for the scorpions, which don't need to feed very often.

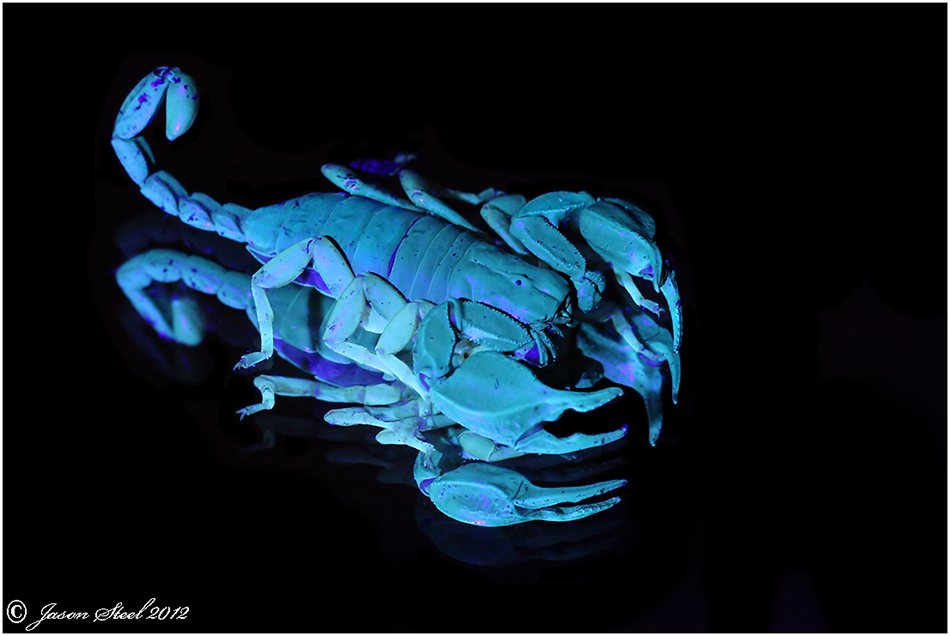

Yellow-Tailed Scorpion glowing under UV light. Found at Sheerness Docks Wall February 2012

Are Yellow-Tailed Scorpions dangerous to humans?

No, the Yellow-Tailed Scorpion is not dangerous to humans or to pets. The Yellow-Tailed Scorpion is a fairly small scorpion species reaching a maximum size of around 20-25mm body-length, and has a total length, including the tail and pincers, of around 35-45mm. These small scorpions have large, powerful pincers for their size, and a short, thin, stinging tail. This tail can usually only deliver a very mild sting to a human. However, the Yellow-Tailed Scorpion is very reluctant to use its sting though, even when hunting these scorpions rely mainly on their powerful pincers to subdue their prey. The effect of the sting to humans is a mere pin-prick to most people and is said to be less painful than the sting of a bee or wasp. The sting usually poses no threat to healthy adult humans at all, although medical advice should be sought if you feel unwell following a sting in case of an allergic reaction.

In southern Europe, where these scorpions are native, there are recent records though of more severe reactions to the sting of the Yellow-Tailed Scorpion by children. One such incident was in the South of France back in 2019, where a 10 year old boy was stung on his hand whilst handling a Yellow-Tailed Scorpion. His symptoms included localised pain, sweating, nausea, abdominal cramps, decreasing muscular strength and an inability to raise his arm above shoulder level. These symptoms past completely after 72 hours with no long-term effects. It is likely that this extreme reaction is partly due to the child's sensitivity to the venom and the time of year the incident occurred. The venom of the scorpion would have been of a much higher concentration than usual as the sting occurred in winter when the scorpion would have previously been inactive for some time. LINK 1 LINK 2

I have handled many specimens of these scorpions myself with my bare hands and have usually experienced no signs of aggressive or defensive behaviour from any of them. However this doesn't mean that I would encourage anyone else to ever handle wild scorpions. It is often quoted that the Yellow-Tailed Scorpions at Sheerness do not sting. Some sources even claim that through some genetic mutation this colony has lost its ability to sting. This is not the case though. It is true that even when hunting, or when caught and handled, the Yellow-Tailed Scorpion does not usually use its sting. However, one large male specimen that I encountered on the Great Dock Wall in July 2024 quickly dispelled that myth. I was attempting to carefully prize the scorpion out from the soft mortar of the wall with a very fine, soft paintbrush. The scorpion was unusually defensive though and kept grabbing hold of the paintbrush with its pincers. After several attempts to dislodge the scorpion it finally resorted to using its stinging tail. The scorpion held onto the tip of the paintbrush and stabbed at the brush with its stinger several times. It certainly wasn't my intention to cause the scorpion any distress and at this point I left it alone to disappear back into the wall.

The general rule is if a scorpion has large, robust claws and a thin tail then it's probably not dangerous to humans. Scorpions with slender claws and thick tails are usually from the Buthidae family, which contains most of the dangerous scorpion species. The notable exceptions to this rule are scorpions from the highly venomous Hemiscorpius genus, which contains around 16 species. Hemiscorpius species have deceptively thin tails and fairly large claws. - LINK

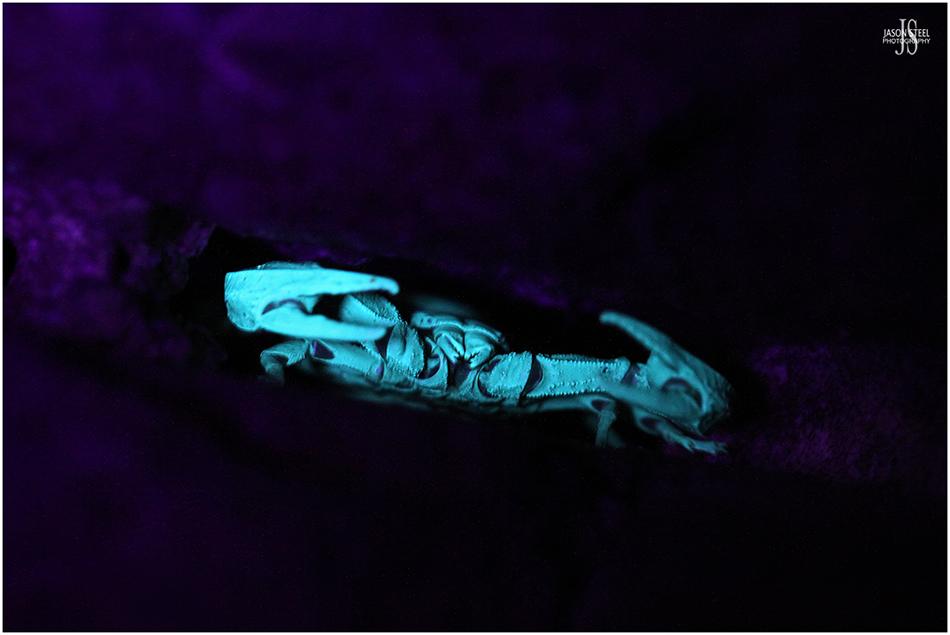

For most of us, that don't have access to the private docks, the scorpions are easiest to find once they become active at night, usually 1-3 hours after the sun has set. Under a UV lamp scorpions glow bright turquoise, making them much easier to spot, whether climbing the walls or hiding in rock crevices.

Yellow-Tailed Scorpion glowing under UV light. Found at Sheerness Docks Wall February 2012

Why do scorpions glow under UV light?

Under a UV lamp scorpions glow a bright turquoise colour, making them much easier to spot, whether they're climbing the walls or hiding in the rock crevices. It is not understood exactly why scorpions glow under UV light, or how scorpions could benefit from this behaviour, but it is known that the fluorescence is caused by the accumulation of a chemical called beta-carboline within the exoskeleton of the scorpion, which glows under UV light. One theory is that this florescence may help to shield scorpions from the harmful UV rays emitted by the sun by converting UV light into harmless visible light. It is also possible that the emitted glow from UV light could attract moths and other insects that scorpions prey upon. Another theory is the glow could help male scorpions when they are searching for potential female mates. Other scientists believe that the florescence may be purely by chance of evolution and may have no significant purpose at all.

On 2nd September 2024 Phil Haynes shared a series of photos on Facebook of an interesting occurrence at Sheerness. A woodlouse was photographed walking along the surface of the Old Great Dock Wall. Unknown to the woodlouse a Yellow-Tailed Scorpion was hidden away in the cracks between the bricks of the wall, with its pincers protruding, in the scorpion's typical ambush pose. When the woodlouse was directly beneath the scorpion it suddenly altered its direction and made a 90 degree turn. It then proceeded to walk directly into the grasping pincers of the scorpion. Was the woodlouse somehow attracted to the scorpion? Could this be a demonstration of the scorpion's UV fluorescence attracting its prey? - LINK

Scorpions are not the only invertebrates that glow under UV light though. Some species of Opilione, or Harvestmen, are also known to glow under UV light. I have personally tested this claim by shining my UV torch on several harvestmen that I have encountered when I've been out surveying for scorpions at Sheerness. Unfortunately none of the Harvestmen specimens I have tried my UV light on exhibited any degree of glow whatsoever. It is unlikely that any of the British species of Harvestmen possess this unusual trait. Elsewhere in the world species such as Pachylus chilensis, from southern Chile, can exhibit a strong glow comparable to that of a scorpion. - LINK. The Ecuadorian Harvestmen (Eucynorta sp., Cosmetidae) is another such example of a invertebrate that fluoresces when exposed to UV light. LINK. The natural world even extends this amazing behaviour to certain species of reptile too. The Namib Sand Gecko, Pachydactylus rangei, of Namibia and South Africa, has been discovered to display an amazing fluorescence under UV light. - LINK LINK 2

Yellow-Tailed Scorpion glowing under UV light. Found at Sheerness Great Dockyard Wall February 2012

As scorpions grow they periodically shed their hard exoskeleton, usually in one complete shell. The few hours following a shed of the old exoskeleton are quite a dangerous time for the scorpion until the new soft shell hardens up. The old discarded shell still glows under UV light however the new shell will not glow immediately but the fluorescence slowly returns as the scorpion ages and the beta-carboline begins to build up in the new exoskeleton once again.

Yellow-Tailed Scorpion glowing under UV light. Found at Sheerness Great Dockyard Wall February 2012

Yellow-Tailed Scorpions are not generally a communal species and cannibalism does occur if keeping more than one of these scorpions in the same enclosure, just as it does in the wild. Following mating, which usually occurs in June, July and August, the long gestation period of the female scorpion is between 10 and 14 months, depending on the temperature and the quantity and quality of food available. The female then gives birth to the fertilised eggs when they are ready to hatch. Once laid the eggs hatch immediately and the number of tiny scorplings can range from 4-30 individuals, that are born soft and white. The female carries these tiny scorpions on her back until they are too large to all fit on her back. This can vary from one to eight weeks. Other sources claim that the scorplings only hitch a ride on their mother's back until they have their first moult, which typically occurs when the young scorpions are around 6 days old. Excellent photos of a female Euscorpius sp. carrying her newly hatched scorplings can be seen here: LINK

As with many species of spider it is not unusual for a mature male Yellow-Tailed Scorpion to stand guard over a viable female mate until she is mature and ready to to copulate. At this stage the male will hold onto the tips of the female's pincers and the two scorpions will begin to circle each other in the "dance of the scorpions". The male will then deposit his sperm-sac on the ground and drag the female until she is directly over it. The female will then collect the sperm package through her sexual opening. Due to the long gestation period female Yellow-Tailed Scorpions will only mate once per year, and not every year. Males may mate with several different partners in a single year, but females will always choose the larger and more dominant males to mate with.

Scorpions have a very basic digestive system. All prey is caught using the powerful pincers and then brought to the jaws, where it is effectively chopped into very fine particles and reduced to liquid form that can be sucked up into the mouth of the scorpion. As with snakes the venom of some scorpion species not only stuns or kills its prey but may also aid with the digestion process too. Prey items are usually eaten head first and one meal generally takes several hours to consume.

Yellow-tailed Scorpion, Euscorpius flavicaudis.

So what does the future hold for the Yellow-Tailed Scorpions in Sheerness?

Sheerness Docks is privately owned is is therefore always at risk of being sold, or partially sold for redevelopment. Parts of the docks have already been converted into residential accommodation and there have been additional plans to turn more of the docks over to further development for housing. In 2002 Dr Tim Benton, who had been studying the Yellow-Tailed Scorpions at Sheerness for a decade, expressed his serious concerns over plans to convert some of the dockyard buildings into residential flats. LINK

In June 2009 a planning application by Dockyard Buildings was successfully fought off following a local petition started by the founder of the Blue Town Heritage Centre, Jenny Hurkett. The proposed application had already been declined once before but revised plans were submitted, which involved converting a historic dockyard building into 26 residential units and building a new development of another 69 residential units, with a car park within Sheerness Docks. Access for the new development proposed knocking a large hole through the historic Great Dockyard Wall, which is currently afforded legal protection as a Listed Structure. Even the RSPCA voiced concerns about the potential risk to the Yellow-Tailed Scorpions should the proposed development get approval. The proposed application was eventually withdrawn to allow the plans to be reworked before being resubmitted again at some point in the future.

Unfortunately, despite being resident at Sheerness Docks for over 150 years Natural England has confirmed that Euscorpius flavicaudis is classed as a non-native species in Great Britain and is therefore not protected under UK Law from being harmed, killed or removed. These scorpions could swiftly, and perfectly legally, be removed by developers spraying the site with pesticides if they stood in the way of future development or deterred potential buyers from investing in their new riverside flats.

There are various sources on the internet that report other alleged sightings of these scorpions in the UK, from various sites. These claimed sightings include: Harwich Docks, Pinner, Chatham Docks, Tilbury Docks, Portsmouth Docks and Southampton Docks, Swanage pier in Dorset, as well as Whitemoor and Ongar Underground Station. Even if there is any truth to the historic existence of scorpion colonies, at any of these mentioned sites, none of these scorpion colonies have managed to survive for many years before dying out. The commonly reported scorpions at Ongar Railway Station are discussed further below.

Yellow-Tailed Scorpions were also allegedly sighted in 2012 on Erith Pier, in SE London, by night fishermen. However I have since thoroughly investigated this Erith site in ideal conditions and there were no scorpions present there in 2020.

In 2015 a number of Yellow-Tailed Scorpions were allegedly collected from a stone wall at the bottom of a residential garden in the coastal town of Seaton, East Devon. As usual there are no photos or other evidence of there being any truth in these claims.

There are also two unconfirmed records of single specimens of Yellow-Tailed Scorpion found in the UK on the NBN Atlas website:

First: Yellow-Tailed Scorpion found in church grounds of Croydon Minister, in South London. 2nd July 2014. LINK LINK 2

Second: Yellow-Tailed Scorpion found on a farmland site in Charltons, Saltburn-by-the-sea, Cleveland, North-East England. 8th July 2009. LINK

A TikTok post shared in August 2022 featured a slide show of Yellow-Tailed Scorpion images, including some of my own, photographed at Sheerness. The post attracted many comments from members of the public. Within these comments were many claimed sightings of scorpions at various parts of the UK. These included: Exeter, Canvey Island, Hadleigh Castle in Essex, Skegness, Sea Wall in Plymouth Dockyard, Dover Dock Walls. Upon my request he post was removed by TikTok as it had used my scorpion images without my consent.

Accidental Imports

Scorpions do regularly find their way into the UK as accidental imports. These hitch-hikers can sometimes be found in imported building materials, fruit and veg, or hidden in luggage.

On 22nd November 2024 a small, and relatively harmless scorpion, Euscorpius species, was found in a property in the St Helens area, in Merseyside (WA10 3LZ). Not many details were given but the scorpion is believed to have been accidentally brought over here from eastern Europe. - LINK

On 21st November 2024 a large scorpion was found in a bunch of pre-packed bananas, at the Birmingham branch of Tescos. The bananas had originated from Colombia, in South America. The sighting was shared on the Insects & Invertebrates of Britain and Europe Facebook group, where it was identified as the Slender Brown Scorpion / Brown Bark Scorpion, Centruroides gracilis. Centruroides gracilis is from the family Buthidae, and has a fairly potent venom. Males of the Slender Brown Scorpion can reach over 15cm in total length. The smaller female can still reach around 10cm. Tesco called in Rentokill to deal with the scorpion, so it was probably destroyed by the pest-control firm. - LINK

On 15th September 2024 a post was added to the British Spider Identification group on Facebook requesting the ID of a scorpion that had arrived in the UK as an accidental import. The scorpion arrived in Basingstoke, as an isolated specimen, hidden in a parcel that had been sent from China. Unfortunately when the parcel was opened the scorpion ran out towards an inquisitive cat. The owner of the parcel panicked and struck the scorpion dead to protect their cat. The scorpion was identified in the group as a potentially dangerous species, the Chinese Scorpion, Olivierus martensii, from the family Buthidae. - LINK

On 2nd September 2024 Chris Hamilton, of the Amateur Entomologist's Society, reported on the Facebook group having previous correspondences with a contact at the Bonded Warehouses at Chatham Docks, in Kent. Chris reports that the contact verbally confirmed the presence of small scorpions being established at the docks. Unfortunately access to the docks could not be granted and no photographic evidence was available to support these claims. - LINK. As usual the conversation included many unsubstantiated claims of scorpions being present elsewhere in the UK, including a comment from one person claiming there were "loads around the outskirts of Dover docks and bottom of the cliffs".

On 23rd July 2024 a scorpion was discovered by a group of roofers in a pallet of roof tiles that had travelled from South America before being discovered in Devon. The roofers believed the scorpion to be a highly venomous Brazilian Yellow Scorpion, Tityus serrulatus. The scorpion was rehomed by the Plymouth Reptile and Aquatic, in Cattedown. Plymouth Reptile and Aquatic boss Mark Craddock claimed the scorpion was a "Common European Scorpion" despite arriving in a box from Brazil. The Common European Scorpion, Buthus occitanus, is a species from the highly venomous family Buthidae, but the toxicity levels, and the effects of its venom, vary within this species depending on the geographic location it originated from. Whilst Buthus occitanus does have the colouration of the harmless Euscorpius flavicaudis the overall shape, the width of the tail, and the size of the pincers make it easy to distinguish between the two species, one being potentially dangerous and the other completely harmless. - ITV LINK, BBC LINK

On the 12th July 2024 The Mirror reported on an unidentified scorpion species that hitched a ride in the luggage of a couple from Streatham, in London. The scorpion had survived the long journey from Mexico and quickly scurried across the floor as the couple unpacked their suitcases after returning from their holiday. The scorpion was captured and collected by the National Reptile Rescue Centre. - LINK

On 25th August 2023 a sighting was shared on Facebook of a small, dark scorpion found in Halifax. From the images provided the scorpion could be identified as being from the Euscorpius or Tetratrichobothrius genus, but couldn't be identified to species level without close examination. It is likely that the scorpion was either Euscorpius flavicaudis / Tetratrichobothrius flavicaudis or Euscorpius italicus. - LINK

The post generated the usual responses from folk claiming to have seen scorpions, or heard rumours of scorpions being seen, at various parts of the UK, including Oxfordshire and Bristol Docks. There was one interesting contribution to the conversation from a lady who found a small scorpion living in her fireplace in the New Forest area, near Lymington. The sighting included a photo of a small, dark scorpion with pale brown legs. The specimen lacked the yellow stinger of Euscorpius flavicaudis / Tetratrichobothrius flavicaudis, so was likely to be a different Euscorpius species. - LINK

On 5th February 2023 a small scorpion was found in a South London house. The finding was shared on Twitter and an ID was requested. An exact ID couldn't be given from the photo provided but the scorpion could definitely be identified as a species from the family Buthidae. It's unknown how this scorpion came to be in the UK but it was collected by pest controllers and removed.. - LINK

Ongar Underground Station scorpions

The scorpion population at Ongar Underground Station was once featured in the BBC's TV program, "Wildlife on One" back in 1979, but this "wild" population of scorpions was later reported by The Independent in 1995 to have been a hoax orchestrated by the station foreman "Fred" who deliberately released five scorpions, bought from a local pet shop in Camden. The scorpions may have bred, or one of the released specimens may have been a gravid female, but some former employees at the Railway Station, and some visitors and local residents, claim the end result was a small population of more than a dozen scorpions that lived in the brickwork of the station for several years, before eventually dying out.

The Independent Newspaper article Sunday 9th July 1995

"At its peak in 1971, 750 passengers were making the return trip. But even then the track was hardly an economic proposition although the staff did their utmost to drum up business. In 1965, an Ongar station foreman bought five (harmless) European scorpions in a Camden pet shop and let them loose in his goods yard. This formed the basis of one of the few scorpion colonies in Britain, which became an attraction. The staff kept quiet about its real origins, and encouraged speculation that it arrived in a banana van in the 1860s."

Dean Sullivan, a former employee at Ongar Railway Station during the 1960's and 1970's, claimed on the former online forum 'www.districtdavesforum.co.uk' that when David Attenborough arrived with a BBC film crew to record the Ongar Railway scorpion population they were unable to find any "wild" scorpion specimens at the station. This former employee also claims that the film crew brought their own captive-bred scorpions, which they filmed and then claimed were found living wild at the Ongar Railway Station. See report here.

Wikipedia.org - Ongar Railway Station

"The sand drag at the very end of the rails — intended to help slow trains that overshot the stopping mark — was said to be home to a breed of harmless scorpion and featured in a 1979 episode of the BBC's Wildlife On One. They had been released there by a station foreman who was a keeper of exotic pets."

Alex Hamlyn covered the story of the scorpions at Ongar Underground Station on the website "strangebritain.co.uk".

Yellow-Tailed Scorpion photographed on a mirror.

Other Scorpion information.

Despite the dangerous reputation that scorpions have, due to their venomous sting, out of the approximately 2500 species of scorpion found throughout the world it is thought that only about 104 species are considered to be any real threat to healthy adult humans if stung. Scorpions are one of the most resilient creatures on the earth. They are capable of surviving fairly low temperatures and extremely hot temperatures, such as those experienced in dessert environments. During US nuclear testing, both scorpions and cockroaches were found surviving near ground zero showing no adverse effects from the radiation. One species of scorpion, Orobothriurus crassimanus, has been recorded at an altitude of 5550 metres above sea level where oxygen levels are very low and many creatures could not survive. Scorpions are also one of the species of terrestrial life-forms that usually survives flooding. Tests have shown that many species of scorpion can survive being submerged in water for several hours, due to their ability to slow their metabolism down, enabling them to retain sufficient oxygen supplies in their body. Some scorpions can last indefinitely without water and obtain the necessary fluids to survive purely from their occasional prey.

Yellow-Tailed Scorpion photographed on a mirror.

Scorpions are not insects, but they are classed along with spiders and harvestmen as arachnids. They are very basic creatures and early fossil records show that scorpions have been on the earth for over 400 million years! Early Sea Scorpions, that could have been as long as 2.5 metres, were capable of walking on land as well as living beneath the water, like modern crabs. There is even consideration over whether these ancient scorpions may have been one of the first creatures to leave the sea and begin living a terrestrial existence. - LINK

There are others, like Kent postman Jason Steel who has won awards for his nature photography. The pictures of Sheppey scorpions on his website www.jason-steel.co.uk are stunning. But he uses macro lenses and stuff. I tried using a flash on one of mine but I think that just frazzled the poor thing. For those thinking of trying to 'pap' a scorpion, Jason offered these tips: "To get sharp images you are going to need your camera mounted on a tripod and you'll have to wait for the scorpion to stand still for a few seconds, which is something they don't often do when they out in the open and exposed to predators. "Wildlife photography takes a great deal of patience and dedication. You can use an off-camera flash to take more natural-looking images but you are still going to need a torch focussed on the scorpion so the camera can focus properly in such dark conditions. "Having a friend to hold the flash and torch for you while you concentrate on taking the photos makes things much easier."

All Photographs on this page were taken using the Canon 40D, Canon 7D, Canon 7D mkii and Canon 5D mkiii cameras and the Canon 100mm 2.8L IS, Canon 70-300mm IS L, Canon 17-85mm IS, Canon 15-85mm IS, Venus Laowa 15mm f/4 Wide Angle 1:1 Macro, and Raynox 250 lenses.